News

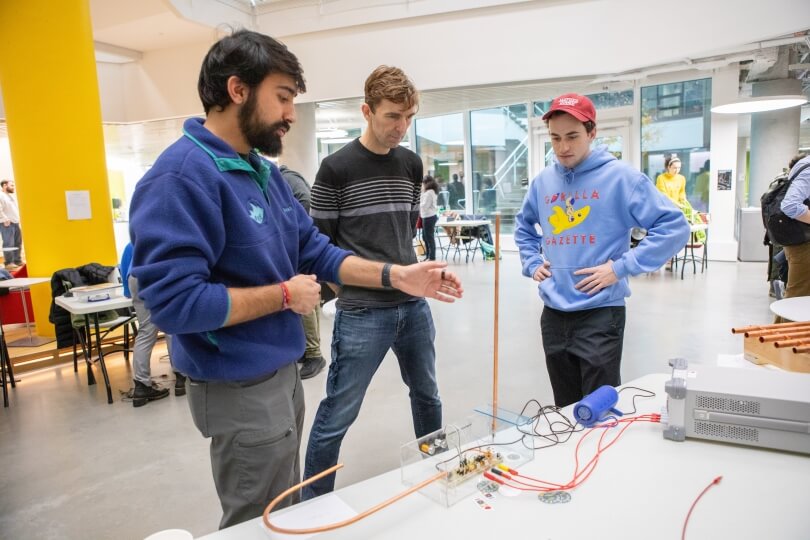

Vikram Singh and Ethan Jasny demonstrate their theremin for Robert Wood, Harry Lewis and Marlyn McGrath Professor of Engineering and Applied Sciences (Eliza Grinnell/SEAS)

Walking into the GenEd1080 Festival is like entering a bizarre orchestral pit. A wall of sound immediately greets you, but where an orchestra might be in unison, here the beauty is in the disharmony, the variation of all the final students projects of “GenEd1080: How Music Works: Engineering the Acoustical World.”

The acoustic notes of a recreated ancient instrument mix with the classic rock twangs of a homemade electric guitar. A theremin emits its eerie, otherworldly warbles just a few feet from one of the longest copper horns you’ve ever seen, its shrill, sharp notes blasting almost deafeningly through the air. The ringing sounds of liquid-filled glassware echo in between percussive beats from drums or drum simulators.

“The cacophony is really what makes us happy, hearing all the noises coming from their instruments,” said course instructor Robert Wood, Harry Lewis and Marlyn McGrath Professor of Engineering and Applied Sciences at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS). “That’s joy to me.”

GenEd 1080 takes students of all years through the physics and engineering principles underlying sound, acoustics and musical instruments. Taught annually in the fall, the course caps off with a final project in which students are given nearly free reign to design something that utilizes the lessons they’ve covered throughout the semester. Projects are displayed at the GenEd1080 Festival at the Science and Engineering Complex, where judges circulate, score and award prizes to the top instruments.

“A lot of the exercises that they do throughout the semester are more traditional, but there are a couple of instrument build projects that allow them to open up, even though there are still constraints,” Wood said. “The final project is totally open, so that’s where I think their creativity can really shine through.”

SKELETON GUITAR

Carrying around full-sized guitars can be awkward, so third-year students Bradley Shearer and Kainoa Paul decided to build something smaller, more stripped down. Their final result: the skeleton guitar, a stripped down version whose wooden body is only half the size of a traditional guitar, and consists of two flat wooden panels, allowing the electric wiring underneath to be fully visible. Despite its size, the guitar can still connect to an electric amp and play just as strongly as a full-sized electric guitar.

“I’d done a little bit of woodworking before, but the detail and precision we’ve been able to do has improved dramatically,” said Shearer, an economics concentrator. “From an electronics perspective, I’d never built a circuit before or done any soldering, and those were both required for this project.”

Shearer and Paul, an integrative biology concentrator, were awarded “Instrument most likely to be featured in a band.”

Bradley Shearer plays his skeleton guitar (Eliza Grinnell/SEAS)

Ricardo Fernandes Garcia and Bimba Carpenter display their copper trombolo and trombolong (Eliza Grinnell/SEAS)

TROMBOLO AND TROMBOLONG

As they were requesting supplies for their project, Bimba Carpenter and Ricardo Fernandes Garcia wound up with a 10-foot-long copper pipe. They could’ve cut it down to size, built a more traditional brass instrument with it but, they asked, where’s the fun in that? So instead they decided to use all 10 feet to create the trombolong, which they paired with a smaller trombolo, a variation of the slide trombone. And rather than drill holes into the pipe, they built a silicone diaphragm, which depending on the applied pressure would change the pitch of the sound emitted from their instruments.

“I personally love building things,” said Carpenter, a third-year student concentrating in art, film and visual studies. “To make something this obnoxious that’s home-built is pretty fun. It was a really fun way to apply the concepts of this course. Papers are great for research, but to actually get to apply the concepts is really cool.”

Surprising no one in attendance, the duo won the “loudest acoustic instrument” award.

MUSICAL WHACK-A-MOLE

Rather than build an instrument, Beamlak Birhane, Madeleine de Belloy and Joel Kizito decided to create a game. The result: Musical Whack-a-Mole, in which a group of students don construction helmets with buttons that correspond to simulated percussive beats. A connected laptop plays a sequence of beats, and one player has to hit the correct button in the correct order, and with the correct rhythm to repeat the sequence. The game is reminiscent of both whack-a-mole and Simon, the classic children’s toy.

“The idea of having a helmet and a button translates well to percussive instruments, because each beat could represent like a kick drum or snare drum,” said Birhane, a second-year studying computer science and applied math at SEAS. “As much as I love music, I took this class to learn how to turn an idea into reality. A lot of the course material, especially prior projects, made it much easier to plan and execute.”

The trio, all computer science concentrators, won the “Most interactive project” award.

Beamlak Birhane, Madeleine de Belloy and Joel Kizito wearing the helmets of their Musical Whack-a-Mole game (Eliza Grinnell/SEAS)

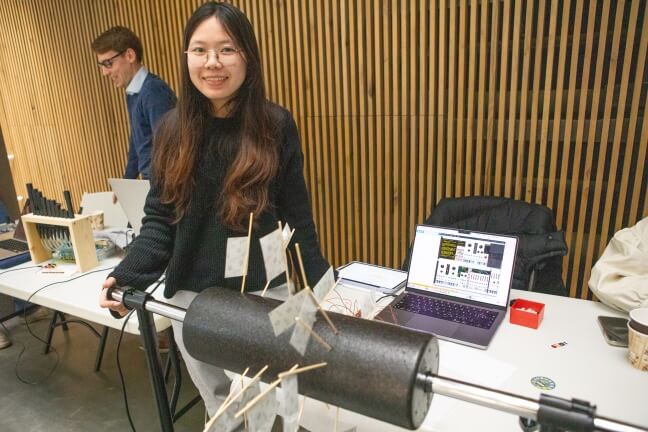

Siyuan Zhou with her Polaroid displayer piano (Eliza Grinnell/SEAS)

POLAROID DISPLAYER PIANO

Siyuan Zhou, a first-year student studying applied math, wanted to build not just an instrument, but a multisensory device that incorporated both visual and auditory displays. Inspired by old-fashioned player pianos, Zhou created a roller, to which she then attached Polaroid photos via little sticks. As the roller rotates, those photos then make contact with force-sensitive resistors, which play notes.

“People no longer use these kinds of instant cameras,” Zhou said. “All our pictures now are just stored on our phones, and we don’t look back on them. Memories fade away, so this is a great way to show the Polaroids that showcase the moments when they were taken.”

The end result is a backing melody to the moments of one’s life.

“I’m not really an engineering student, but the description of this course really attracted me,” she said. “I’m very into music, so I wanted to learn how to make it.”

Topics: Academics, Electrical Engineering, Materials Science & Mechanical Engineering

Cutting-edge science delivered direct to your inbox.

Join the Harvard SEAS mailing list.

Press Contact

Matt Goisman | mgoisman@g.harvard.edu