Oni Blackstock, A.B. '99, MD '05

Oni Blackstock had no idea how much computer science would benefit her career in healthcare when she picked it as a concentration at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS). The daughter of a Harvard Medical School (HMS) graduate, Blackstock always intended to go pre-med and eventually become a doctor herself. She initially chose computer science because of an AT&T scholarship she’d secured that required her to study either engineering or CS.

Two decades later, computer science remains a vital element of Blackstock’s work. Whenever she takes on research projects, the coding she uses in statistical analyses is built on her coursework at SEAS. When she served as assistant commissioner for New York City’s Bureau of HIV, she often had to work with large data information systems and data sets, drawing on concepts such as data security and privacy. Even now in her work as founder of Health Justice, a social impact consultancy focused on improving racial equity in public health and healthcare systems, she often finds herself delving into CS topics such as generative artificial intelligence, which she believes if deployed correctly could be quite beneficial for more equitable patient care.

“If someone had told me when I finished med school that I’d be doing this work, I wouldn’t have been able to imagine it,” Oni Blackstock, A.B. '99, MD '05. “When you’re in school, you sometimes only see one way to do things. But I get to use lots of skills that I’ve accumulated through college and medical school. It’s been exciting to lead my own enterprise, but also kind of scary.”

Blackstock’s mother has inspired many of her career choices over the years. Dale Gloria Blackstock, MD ‘76, worked as a nephrologist in New York City after leaving HMS, and Oni and her twin sister Uché, and Dale and her husband instilled in their daughters a passion for social justice.

“We were always going to protests and demonstrations, but my mother would also take my sister and me to community health fairs, where she’d educate community members about things like kidney disease and high blood pressure,” Blackstock said. “We were very used to seeing her in that space, really enjoying herself and her interactions with community members. While she had a role in a brick-and-mortar clinic, it was also really important for her to meet community members where they were and do outreach.”

When it was time for the Blackstock twins to head to college, there was really only one choice. Uché studied biology as an undergrad here, and joined her sister at HMS.

“Even though my mom had a very different upbringing than I did, she found a really supportive mentor at Brooklyn College and ended up getting into Harvard Med School,” Blackstock said. “She really wanted my sister and I to consider Harvard.”

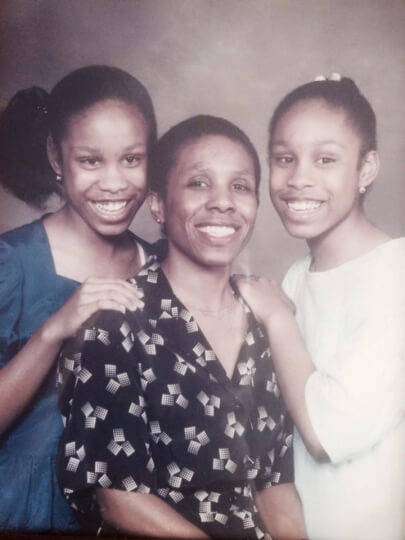

Oni Blackstock, A.B. '99, MD '05, with her twin sister Uché Blackstock and mother Dale Gloria Blackstock. All three graduated from Harvard Medical School.

Blackstock’s mother died from leukemia in the summer after Oni’s second year at SEAS. Earlier this year, Uché published Legacy, a book about her mother, in which she discussed how growing up near a radioactive dumping ground may have led to Dale’s diagnosis. Two of the four such legal dumping grounds in New York City were near predominantly Black or Latinx communities, leading to Uché’s belief that systemic racism factored into her mother’s death.

“That was a really difficult time,” Blackstock said. “Finding people who were supportive and cared was important, and I think they really helped my journey at Harvard.”

After graduating Harvard, Blackstock spent time researching HIV in Ghana and South Africa. She saw major disparities in treatment for different demographics there, and when she came home she realized the same issues plagued the U.S. That led her to take on several initiatives in the New York City Health Department’s Bureau of HIV, including a campaign to help women develop a sexual health plan, investment in more clinics that offered low or no-cost testing and treatment, and initiatives that promoted the message that patients with an undetectable HIV viral load can’t sexually transmit the virus. Such efforts led to a strong decline in HIV-positive cases since 2001.

While working at the Bureau of HIV in New York, then-New York State Health Commissioner Mary Bassett founded an internal reform initiative called “Race to Justice.”

“It focused on addressing the impacts of racism, both internally and outside of the agency,” Blackstock said. “I started the first bureau-based racial equity social justice program in the Bureau of HIV. Just doing that work, I realized I could also do it outside of the agency, where I’d have more control over my time, scheduling and who I work with.”

Blackstock founded Health Justice in August 2020, just a few months into the COVID-19 pandemic. While doing so, she was also part of the city’s COVID-19 response team, as she could see similar disparities in how the pandemic was being addressed in Black communities versus other demographics.

“That was a really interesting but traumatic time,” Blackstock said. “I had a 300-person bureau, and no one had ever experienced anything like this before. I had to make the decision to pull my entire bureau from community-facing work. We had to pivot and innovate and think about how we could reach the communities we serve in a more virtual space. I was often working seven days a week, often 24-7.”

Health Justice works with healthcare systems, public health departments and non-profits to assess racial equity. They gather data through interviews, focus groups and surveys on organizational culture, commitment and programming, and also run sessions with executive team members to make sure organizational leadership buys into and feels ownership of the goal of improving racial equity in healthcare. Blackstock is also starting to design microlearning courses that organizations can take on their own time, and often gives talks about her career trajectory and focus on community-centered, participatory inclusive approaches to healthcare. An upcoming course will focus on artificial intelligence and large language models, which she was first exposed to at SEAS.

“When we lead with equity, everyone benefits,” Blackstock said. “If we create programs and initiatives for the most burdened, everyone can benefit from them.”

Press Contact

Matt Goisman | mgoisman@g.harvard.edu