News

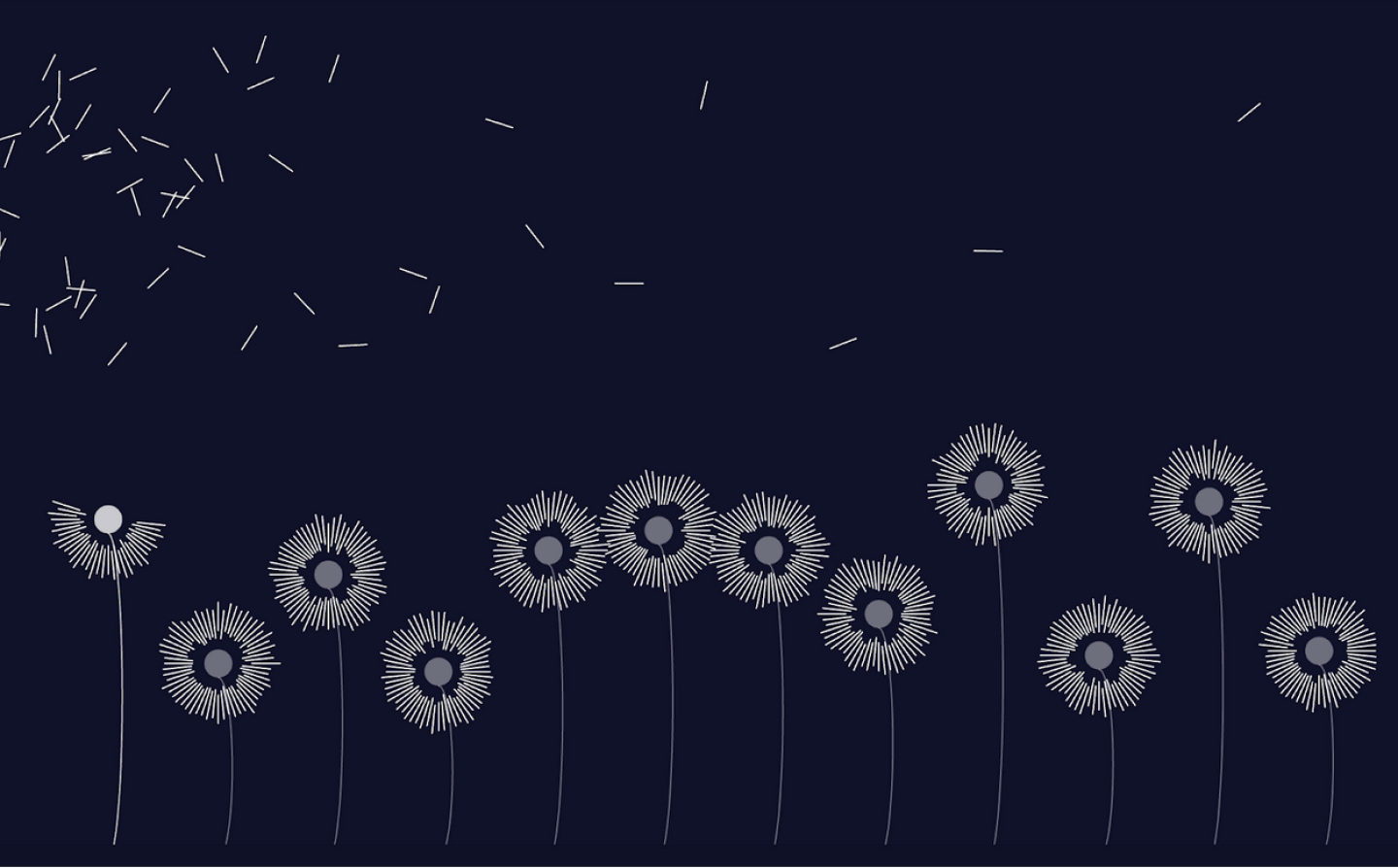

Students discuss "Kyoto Cherry Blossoming," by Cynthia Chen, in a group critique session of "CS73: Code, Data, and Art" at the Science and Engineering Complex. (Matt Goisman/SEAS)

Cynthia Chen grew up making art. She’d draw, paint, and sketch, and over time, the studio became a key piece of her identity.

In her first two years at Harvard, Chen struggled to find a way to combine her passion for the visual arts with her computer science education at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS). Now in her third year, Chen is finally getting to tap into her creative side in “CS73: Code, Data, and Art,” a new course that teaches students how to create art and data visualizations using computer software.

“This course has really pushed my creative bounds and allowed me to connect with that part of myself,” Chen said. “It’s almost a dream course for me - everything I’ve wanted to learn all at once about the intersection of art, visualization, data analysis and design.”

CS73 is the brainchild of Gordon McKay Professors of Computer Science Fernanda Viégas and Martin Wattenberg. Wattenberg joined the SEAS faculty in Fall 2021 and Viégas followed in Spring 2022, but the two have been exploring the worlds of digital art and visualization together for nearly 20 years through organizations such as the IBM Research Visual Communications Lab and Google’s People + AI Research Initiative.

“It’s a really powerful combination of expressing in a computational manner,” Viégas said. “My background is in graphic design, so I love visually thinking about things. Being able to do that through technology, through computation, adds a new dimension.”

Students discuss Max Allison's "News Is __" in a group critique session of "CS73: Code, Data, and Art" at the Science and Engineering Center." (Matt Goisman/SEAS)

“There’s kind of a separation between the world of STEM and the world of humanities that does not need to be there,” Wattenberg added. “We’re trying to teach the importance of understanding how a program you write is perceived by other people. To learn what it’s like for someone else to use code that you wrote is a central maneuver of writing usable, enjoyable, and ethical software.

Classes meet twice a week: lectures on Thursdays, and group critiques the following Tuesdays. Lecture topics range from the coding software students will use to create their pieces, to specific aspects of visual arts such as color palette, typography and conveying emotion.

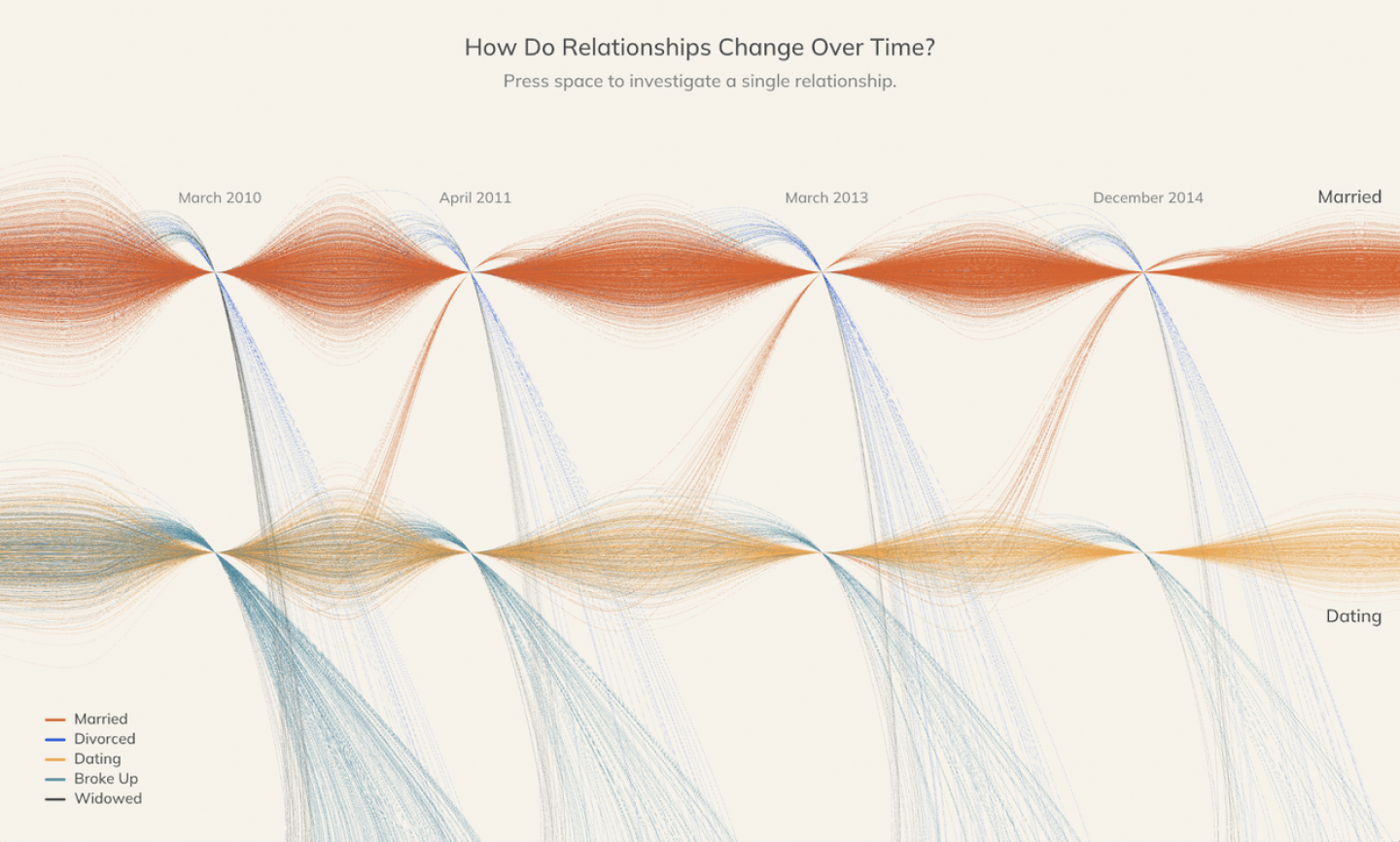

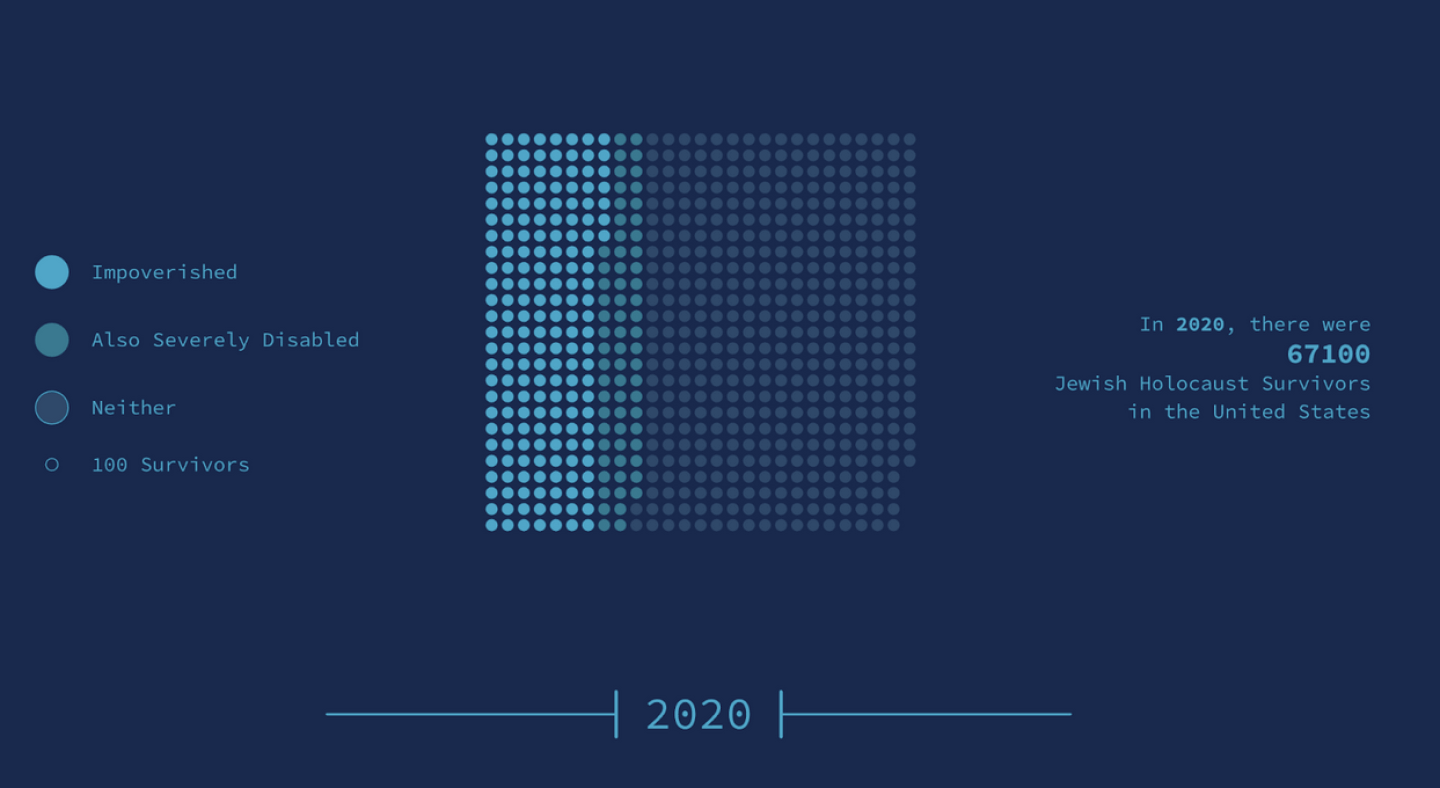

Students then have the weekend to create new pieces. Sometimes these are graphs and charts made to visualize data around a specific topic, but sometimes they’re abstract pieces of art.

“For the first five weeks of the class we all did purely artistic pieces and abstract art,” said Daniela Garcia, a third-year statistics student focusing on data science. “That was very new for me because I’d yet to do something like that with respect to computer science. It was a very unusual but very exciting way to think about creating art, and I liked that it was something I’d never tried before.”

Critique days consist of large group discussions. Students push their tables into large clusters, then one at a time present their new pieces. Other students are then free to comment on everything from subject matter to color and font choice.

"Twitter Insults," by Michelle Liu, is discussed in a group critique session for "CS73: Code, Data, and Art." (Eliza Grinnell/SEAS)

“I really like that this is an outlier in the curriculum that focuses on the intersectionality of creativity with computer science and allows people to expand more on those topics of art and design,” said Trevor DePodesta, a first-year student planning to study computer science. “I used to produce one or two artistic pieces a month. I’ve been here for a month, and I’ve produced 11. The rapid speed at which I’m forced to reiterate my work is really expediting the progress I’m making.”

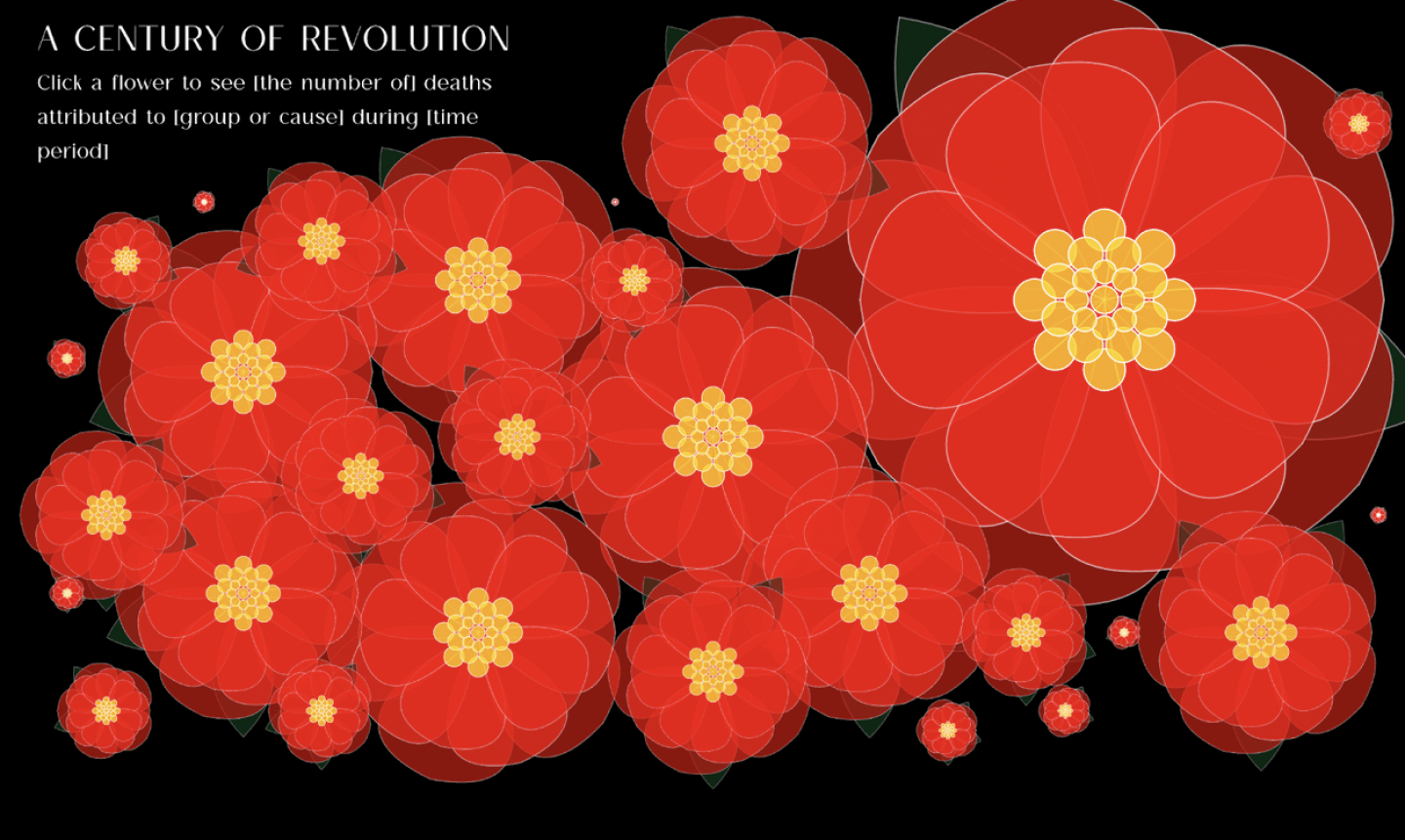

Communication is a central theme in CS73. The best research data in the world doesn’t matter if it can’t be conveyed in a way that’s easy to understand, often by people without the researcher’s expertise. Visualization is critical to making data comprehensible and impactful.

“When you’re creating a data visualization piece, you’re authoring a piece of rhetoric,” Viégas said. “You have power when you choose the colors, how the typography will lay out, what interactive affordances you bring to the piece. Part of the educational arc here is for students to understand that you’re not just putting marks on a computer screen. You have to intentionally use these visual tools, because everything there is going to be a choice, and every choice is going to communicate something to your viewer.”

Wattenberg and Viégas sit among the students during group critiques. They make sure everyone gets a chance to present, and two months into the semester, the discussions are largely self-directed by the students. The duo will give their own critiques on each piece, but student enthusiasm for the material has reached the point where the teachers don’t have to ask much beyond “What do we think?” and “Who’s next?”

Martin Wattenberg, Gordon McKay Professor of Computer Science and one of two teachers for "CS73: Code, Data, and Art," participates in a group critique session at the Science and Engineering Complex. (Matt Goisman/SEAS)

“The students are so good, and the course would not work without their level of insight and perceptiveness,” Wattenberg said. “Whoever’s work is being critiqued is obviously learning from the comments, but I also think students are learning to give good critique and make good comments. That’s a skill that I think is not only an important intellectual skill, but also something that will serve you well in any practical, corporate or government setting.”

Given their history together, Wattenberg and Viégas knew this would be the first class they co-taught at SEAS. Wattenberg could see the interest from students as a concentration advisor last year, but there was still some worry that this class wouldn’t draw interest from a student body used to focusing on technical skills and problem sets in their CS classes.

Once registration opened, their fears quickly disappeared.

“The course had a long waiting list, so that answered our first question as to whether there was enough interest,” Viégas said. “It’s been really exciting to see the arc that students in the class have been following. I really feel like they are picking up the skills, and you can see it in the pieces they’re creating week after week.”

Scroll through the slideshow below to see more examples of student compositions and discussions from CS73.

Topics: Computer Science

Cutting-edge science delivered direct to your inbox.

Join the Harvard SEAS mailing list.

Press Contact

Matt Goisman | mgoisman@g.harvard.edu