Treatment for breast cancer often involves three steps: chemotherapy, surgical removal of tumors, and radiation therapy to target any tumor cells that may have been left behind.

Radiation treatments are intended to reduce the chance of cancer recurrence. but in about 20 percent of cases tumors still return.

Clinicians have gotten much better at surgery, chemotherapy, and targeted radiotherapy over the past few decades. Marjan Rafat, Ph.D. ’12, wondered why this rate of recurrence remains so high.

“Are we just missing tumor cells, or are the cells coming from elsewhere?” said Rafat, who earned a Ph.D. in bioengineering from the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences and Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. “I want to understand how normal tissue damage, caused by radiation, could induce circulating tumor cell recruitment back to the primary cancer site.”

She’s investigating this topic at Vanderbilt University, where the Assistant Professor of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering leads the Tumor and Tissue Microenvironment Lab.

Rafat is developing tumor engineering microenvironment models to understand how normal tissue damage can affect breast cancer recurrence. Her team is creating 3D structures from animal cells to study how radiation affects tumor cell movement in vivo while also building 3D hydrogels to explore how radiation damage affects the extracellular matrix, especially its role in influencing cell proliferation and migration.

“A lot of groups focus on the tumor response itself, but we are trying to understand how the bystander effect, the effect from the surrounding normal cells, could actually alter tumor behavior,” she said.

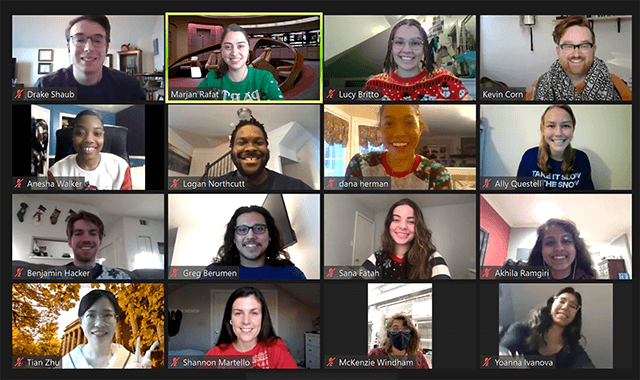

Students working in the Rafat Lab. (Photo provided by Marjan Rafat)

The work is still in its early stages, but Rafat is hopeful this research will produce new knowledge that will help clinicians better treat patients.

For instance, if she and her team discover that a certain type of immune cell is infiltrating and causing the cancer recurrence, perhaps a physician could deliver an agent to change the polarization of those immune cells so they don’t attract tumor cells, she said.

“It is all a matter of understanding these fundamental changes, and then eventually incorporating what we learn into future treatment—not to replace a treatment, but to add to the standard of care,” she said.

Pursuing a career in which she could help people has been a priority for Rafat since her teenage years. Her father worked as an electrical engineer, and Rafat found that she shared his fondness for math and science.

That interest led Rafat to enroll at MIT, where she studied chemical engineering. The spring semester of her freshman year, she dove straight into research, joining a lab that was focused on biomaterials.

While a Harvard graduate student, Rafat (right) mentors then-student Lisa Rotenstein in the lab. (Photo provided by Marjan Rafat)

Because the lab was so small, she had the opportunity to learn many research techniques from senior scientists, like high-performance liquid chromatography and cell culturing.

“In class, I was learning how to think, but in research, I could actually do that with my hands. I could set up experiments. I enjoyed that level of problem solving,” she said. “Of course, there was a lot of failure. There were a lot of boring days. But when I got a positive result, that overshadowed every other issue. I gained a lot of confidence through that experience.”

While many of her peers began industry careers, Rafat’s desire to help people inspired her to pursue a Ph.D. at SEAS, where she joined the lab of Debra Auguste. (Auguste is now a Professor of Chemical Engineering at Northeastern University).

As a graduate student, Rafat focused on designing biomaterials to better treat brain aneurysms. Current aneurysm treatments either involve clipping, where a clinician performs a craniotomy and clips aneurysms at the bud, or filling an aneurysm with coils to help prevent clot formation, but both treatment methods have pitfalls.

“I wanted to find a technique that maximized the benefits of both strategies, where I could fill any shape of aneurysm with a biomaterial that could adhere to the endothelial cell wall but also not require an invasive procedure,” she said.

The complex research posed unique challenges; for instance, it was difficult to synthesize enough of the novel biomaterial to be able to test it, said Rafat. She enjoyed the lab work, but the opportunity to mentor undergraduates really piqued her interest in an academic career.

“Being able to explain my work and get students enthusiastic about the work and interested in research, that was really fulfilling for me,” she said.

Mentorship was important to her, but so was making a positive impact on the lives of others. Several family members and close friends had been stricken with cancer, so she decided to dig deeper into cancer research during a postdoctoral fellowship at Stanford University.

She began studying the impact of radiation on tumors and normal tissue, which fed into her current work at Vanderbilt.

While she continues to explore those impacts from many angles, her research has shown that patients who are immunocompromised for long periods after receiving radiotherapy have a much higher propensity for local cancer recurrence.

The members of the Rafat Lab. (Photo provided by Marjan Rafat)

“We’re not saying that radiation shouldn’t be given. In most cases, radiation does reduce the rate of local recurrence,” she said. “But when you have these other circumstances, like a low lymphocyte count, what else can we do to prevent those cells from coming back?”

In seeking answers to that question, Rafat works closely with medical school researchers and clinicians.

Interdisciplinarity is critical since she and her team must ensure their experiments are meeting criteria important to clinicians . Engineers and physicians sometimes seem to speak different languages, so ensuring both groups understand each other is essential, she said.

While Rafat continues to draw inspiration from the positive effects her work could have on future cancer treatments, her ability to inspire others remains her biggest driver.

“The most rewarding thing is seeing the light bulb go off for my students, seeing that excitement,” she said. “Research can be a slog, but once you make those discoveries, once you get that data you’ve been working so hard for, it feels amazing. Once I see the motivation and the students really working to get over these hurdles, that keeps me going.”

Press Contact

Adam Zewe | 617-496-5878 | azewe@seas.harvard.edu