News

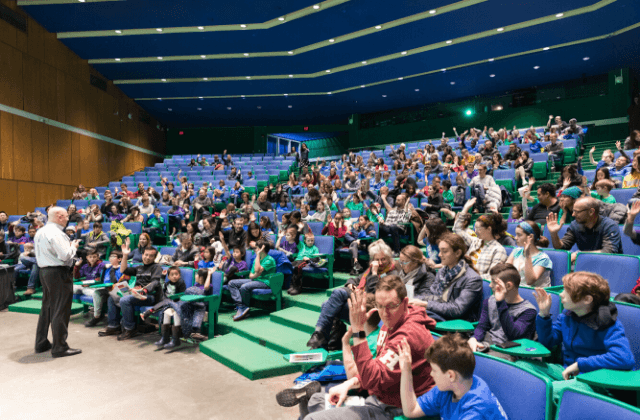

Participants enthusiastically raise their hands after Professor Howard Stone asks "Who likes ice cream?" (Photo by Joshua Chiang/SEAS Communications)

Ice cream was the tasty topic of the annual holiday science lecture presented by the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences.

Originally inspired by Michael Faraday’s Christmas lectures for children at London's Royal Institution in the 1800s, these holiday lectures are designed to create enthusiasm for science. This year’s lecture, titled “Ice Cream for Science: It’s Legen-Dairy!,” explored the scientific principles involved in the making of ice cream, from obtaining the right temperature to generating its creamy texture.

The presenters, Howard Stone, a former SEAS faculty member and now Dixon Professor in Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering at Princeton University, and research assistant Daniel Rosenberg, began by introducing the principles that make ice cream a frozen treat. They demonstrated the different phases of matter by placing a block of ice in a hot pan. As the block of ice sizzled into water vapor, they explained how the movement of molecules changes in each phase from vibrations in the solid phase to free movement in the gas phase.

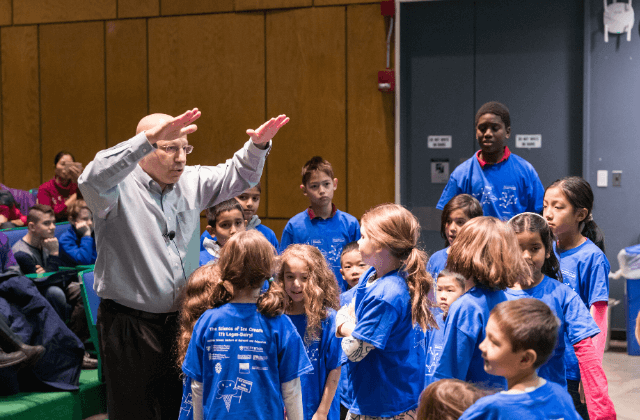

Twenty kids then came to the front of the lecture hall to act out a phase change. They interlocked arms to represent a crystal solid state, moved around to represent the liquid phase, and danced around in the gas phase.

Professor Howard Stone directs participants as they act out freezing point depression. (Photo by Joshua Chiang/SEAS Communications)

The presenters then explained how adding molecules to a solution, such as adding salt to water, disrupts the ability of the molecules to form a crystal structure. This means that it is more difficult for the solution to freeze, which lowers its freezing point. To represent a process called solvation, a group of kids acted as water molecules and tried to surround other kids acting as salt ions, keeping the “ions” from holding onto each other in a crystal structure.

Next, the presenters explained why ice cream becomes crunchy when it is pulled in and out of the freezer too many times. The freezing-melting cycles lead to a process called coarsening. Since small crystals are more unstable than large ice crystals, each freezing-melting cycle causes the crystals in the ice cream to melt and refreeze into larger crystals.

The kids in the audience had the chance to illustrate the coarsening phenomenon. First, a large group surrounded a few kids, who were acting as small ice crystals. Then, they tried to surround much larger groups of kids, representing large ice crystals, and found it to be much more difficult.

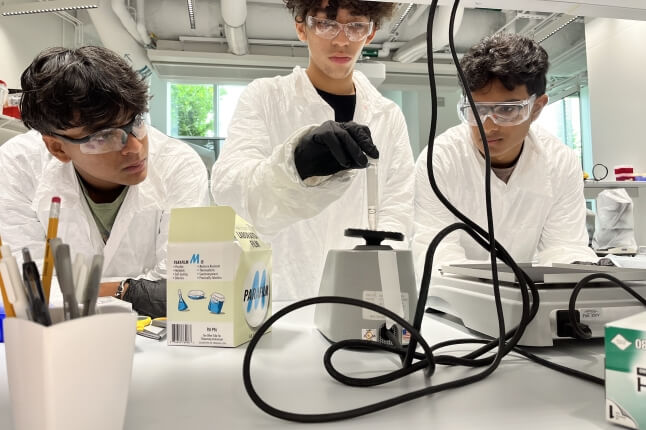

Bags of ice and cream mixtures are passed around to be shaken up by participants to make ice cream. (Photo by Joshua Chiang/SEAS Communications)

A few families were selected to help make ice cream samples during the lecture, so everyone could try a taste at the end. Making the ice cream involved vigorously shaking bags of ice that contained a smaller bag with the ice cream ingredients.

Kids and adults alike were all smiles as they gathered around to try some of the ice cream that was brought to them through the efforts of the presenters, audience volunteers, and of course, a big scoop of science.

Cutting-edge science delivered direct to your inbox.

Join the Harvard SEAS mailing list.

Press Contact

Adam Zewe | 617-496-5878 | azewe@seas.harvard.edu