News

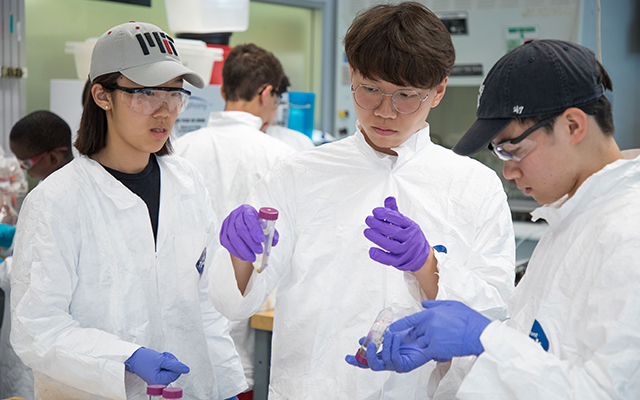

Students in the collaborative Water Engineering and Resource Management Program learn to measure and analyze water quality. (Photo by Colleen Anderson)

Water makes up over 70 percent of the Earth’s surface. But only 1 percent of water is safe to drink, and more people are killed each year by exposure to unsafe water than from war and all other forms of violence combined. Water scarcity and pollution are projected to affect two-thirds of the world’s population by 2025, according to the World Wildlife Fund.

This summer, students participating in a program run by the Active Learning Labs at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS), learned to apply design thinking approaches to real-world water pollution and clean water shortage crises.

During the two-week Water Engineering and Resource Management Program, students from Cambridge, Kenya and South Korea explored both problem solving techniques and the science behind water purification. Beginning with the basics, students focused on the importance of brainstorming and defining the problem. They learned the value of human-centered design and the differences between various design tools, such as basic prototyping versus advanced rapid prototyping techniques. The rest of the week centered around water purification, covering topics such as: water drinkability, helpful or harmful roles of different water constituents, water regulations, and techniques to measure water quality. The first week concluded with a mini design challenge where students built filters to clean water they collected from the Charles River.

“At first I found it a little hard to understand why we had to do what seemed to be simple things,” said Daniel Muthokn, a teacher from the Clay International Secondary School in Kenya. “But by the start of the second week, I understood why we had to get into the nitty-gritty before you go to the big thing.”

The Water Engineering and Resource Management Program challenged students from South Korea, Kenya, and Cambridge to build filters to clean water they collected from the Charles River. (Photo by Colleen Anderson)

During the second week of the program, students took part in a water engineering challenge; three teams chose and researched an issue, designed model prototypes, and then calculated their full-scale potential to solve that issue.

One group focused on solving the water sanitation problem in Makueni County in Kenya, building a prototype they dubbed Har-K. Har-K was a cheap, effective, and easily accessible water filtration system using solar distillation, a process that utilizes energy from the sun to remove contamination from the water. The second group focused on creating an autonomous floating device that uses blue ultraviolet light to kill toxic algae polluting a river in South Korea. This group also designed a separate device to collect the dead algae to be repurposed as a food supplement or incorporated into other products. The final group designed a multiple-tank filtration system aimed at decontaminating large quantities of water from the Nairobi River to help the 200,000 people living in the Mathare Valley of Kenya.

For students Charity Ndoti Mbithe and Rosemary Mutindi Mulei of the Clay International School, it was especially meaningful to not only learn techniques to create clean water, but also design real solutions for issues that directly affect their families in Kenya.

“My group is working on the problem of salinity in water,” said Mbithe. “I am finding it interesting because this is a very serious problem in our country, so I am anxious to learn more and share my knowledge with the rest of the students back in Kenya so that maybe we can use it to solve the problem.”

This program showed students and teachers the value of a hands-on learning experience. Students learned about effective problem-solving and how to treat polluted water, but were then in charge of translating those skills into action.

“We have been able to see a way of teaching whereby the faculty pass the information and then let the kids do collaborative learning, which is a great aspect I will take home,” said Muthokn.

During the two-week Water Engineering and Resource Management Program, students from Cambridge, Kenya and South Korea explored both problem solving techniques and the science behind water purification. (Photo by Colleen Anderson)

Topics: Environment

Cutting-edge science delivered direct to your inbox.

Join the Harvard SEAS mailing list.

Press Contact

Adam Zewe | 617-496-5878 | azewe@seas.harvard.edu