Building bridges, constructing embassies

Construction can be a complex undertaking, often involving a delicate balancing act involving subcontractors, materials, schedules, and budgets. But move that construction site to a distant, developing nation where English is not the main language, add a few layers of federal-government red tape, and challenges start stacking up faster than bricks and mortar.

Few people know that better than Philip Barth, A.B. ’77. As director of construction management for the U.S. State Department, Barth oversees a global portfolio of $14.5 billion in active U.S. embassy construction projects, including about $3.5 billion of new work each year.

“The challenges of seeing things at the macroscopic level are new and different for me,” said Barth. “My work involves stepping back and trying to find ways to improve our efficiency, while negotiating with different entities to get what we need to be successful in our programs.”

Philip Barth with his son, Aaron, A.B. '04, and wife, Debbi. (Photo courtesy of Philip Barth)

He enjoys the global impact of his work, but Barth, now in his 31st year at the State Department, never intended to pursue a career in public service. As a Harvard undergraduate, he nearly pursued a concentration in folklore and mythology before deciding his job prospects would likely be better if he studied applied sciences at the John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences.

Barth harbored an interest in math from an early age, but his greatest childhood passion, which followed him into adulthood, was a yearning to travel the world. His college girlfriend, Debbi (now his wife), shared that passion, so they decided to undertake mission work in the Middle East to foster better cross-cultural understanding.

The newlyweds moved to the West Coast, where Barth pursued a master’s degree in intercultural studies at Fuller Theological Seminary in preparation for their life overseas. As an engineer, he enjoyed this opportunity to stimulate the right side of his brain.

At the same time, he began working part-time at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory. He studied new methods for connecting integrated circuits with controller boards, since traditional soldering techniques couldn’t stand up to the demands of space flight.

“We had zero tolerance for failure,” he said. “We had to build in everything the Jupiter probe would need for its mission because there was not going to be a repair shop along the way.”

After earning his master’s degree, he and Deborah traveled to Jordan with an international NGO. But when a job lead in Jordan fell through a few months later, their dream seemed to be slipping away.

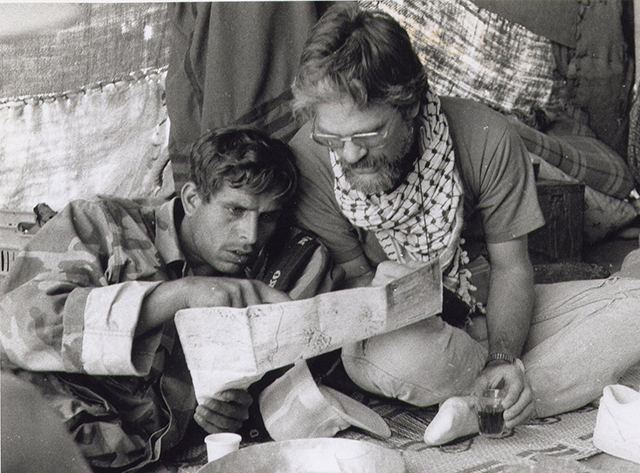

Barth (right) with a Bedouin host in the Wadi Rum valley in Jordan. (Photo courtesy of Philip Barth)

By happenstance, Barth ran into a friend’s neighbor who suggested he apply for a job at the construction site of the new U.S. Embassy in Amman, since the mechanical engineer on the project had resigned.

“It was the perfect timing. Because I was an American and eligible for a security clearance, they were willing to give me a try, even though I had never worked in construction before,” he said. “It ended up being a great opportunity and a career in not only building embassies, but improving security for people serving abroad, and an opportunity to represent the U.S. to host nations.”

Barth worked on the heating and cooling systems for the new embassy, refreshing his memory on lessons from thermodynamics courses as he went. He was intrigued by the technical work, and applied his cultural sensitivity training by building bridges between Americans and locals, especially when the Gulf War intervened in 1991.

The U.S. embassy in Amman, Jordan. (Photo courtesy of Philip Barth)

Afterwards, he worked on an embassy renovation project in Israel, and during this time, he and his wife helped start an English-speaking church for expatriates, where they led the music ministry. Next he moved to Ottawa to finish a new embassy construction project there, and then spent a few years in the Washington, D.C. home office, offering logistical and budget support for projects around the world.

Then 9/11 changed everything.

The terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon came on the heels of the 1998 Africa embassy bombings, and the State Department began investing billions of dollars to improve safety and security at embassies.

“The older priority for embassies was to be accessible, downtown, and near the ministry of foreign affairs and other government offices,” he said. “With the world changing and security becoming a higher priority, we began moving embassies to locations where we could have large setbacks, which meant that we needed bigger properties outside of the city centers.”

Barth’s first assignment under these new guidelines was to build an embassy in Brazzaville, Congo. That nation was recovering from a devastating civil war, so much of its infrastructure remained broken.

Faced with unreliable rail service, Barth’s team shipped materials through the neighboring Democratic Republic of the Congo, and then floated them across a river to the construction site. But with one problem solved, another arose.

The rapidly approaching World Cup in South Africa, and subsequent building boom, caused skyrocketing cement prices. Careful negotiations with local officials challenged Barth’s political skills and patience.

He drew on those experiences during his next assignment in Baghdad, where he worked to consolidate several facilities and expand the embassy.

“Each time along the way, the challenges changed. In Baghdad, for instance, while it wasn’t a war zone at the time, there were a lot of challenges with infrastructure and ministry officials who weren’t too happy with us being there,” he said.

Even his most recent project, constructing a state-of-the-art embassy in The Hague, Netherlands, was not without headaches. He recalls working with a half dozen regulatory agencies to secure approval to build one small bridge for cyclists.

The U.S. embassy in The Hague, Netherlands. (Photo courtesy of Philip Barth)

After completing that project, he returned to Washington to take the helm of the global construction portfolio.

While he faces constant pressure in his new role, especially since the pace of construction is expanding while the budget for personnel is shrinking, Barth continues to find the work rewarding.

“Each project is a chance to start over and work on a new set of problems. But what I also find rewarding is the opportunity to help people resolve their differences and promote a collaborative work environment,” he said. “A lot of our technical people don’t appreciate how important it is to build trust between the different stakeholders on a project. Once that is lost, the entire project suffers. If you are only focusing on the materials and money, without understanding the role of the team, the chance of success goes down.”

And while the path he followed during the past three decades—through more than a dozen different nations—isn’t the one he had intended, the work has enabled him to do what he originally set out to: promote cross-cultural understanding.

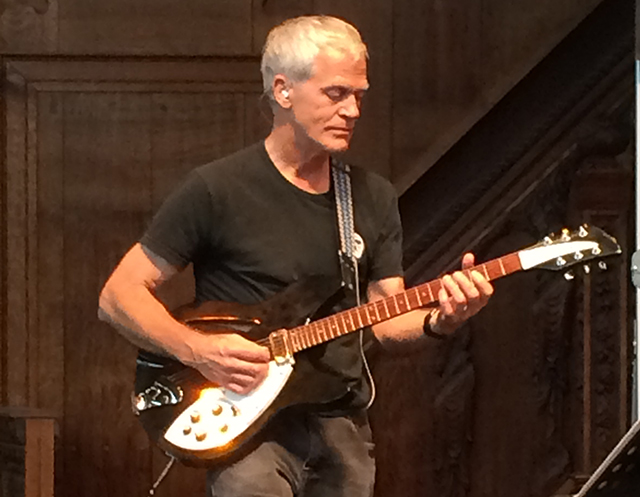

Barth playing guitar at church, where he and his wife participate in music ministry. (Photo courtesy of Philip Barth)

Do you have an interesting story you'd like to share with your fellow alumni? We'd love to hear from you! Contact the SEAS Office of Communications.