News

One-third of transgender individuals were either verbally harassed or refused treatment from a health care provider in 2015, according to the U.S. Transgender Survey. But in the 73 nations where homosexuality is a crime (in eight nations it is punishable by death), injustice is even more pervasive.

How could biomedical engineering play a role in solving some of the multi-faceted issues surrounding health care for trans individuals? Montita Sowapark, A.B. ’19, set out to answer that question through her senior thesis project.

“There is a huge gap in terms of the provision of inclusive and accessible health care for LGBTQ+ communities, especially when you are also dealing with intersecting obstacles like race, class, and disability,” said Sowapark, a joint concentrator in women and gender studies and biomedical engineering at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences. “Across the board, there is still very pronounced and deeply entrenched stigma throughout the field of health care, especially for trans individuals.”

For her two-part thesis, she began by studying how the sex/gender system affects the health and wellbeing of LGBTQ+ individuals in Thailand, and then developed a medical device to make the dilation process easier for trans individuals who have undergone gender-affirming vaginoplasty.

Sowapark conducted 32 interviews to analyze how people’s gender identities and sexualities are treated in different ways throughout Thai society—in the family, schools, the workplace, and health care settings—and how those disparities implicitly and explicitly marginalize LGBTQ+ people.

“Thailand has a gender equality act and is considered rather progressive among Asian countries in terms of social norms and legal institutions. However, there is often tolerance, but not acceptance,” she said. “Many people think Thailand is a paradise for LGBTQ+ individuals, but when you talk to people on the ground, there is a real sense that this is just a fantasy and it doesn’t play out in people’s lives.”

One area where Thailand is a leader for LGBTQ+ health care relates to gender affirming vaginoplasty, a procedure where a surgeon creates both an outer and inner vagina by using skin and tissue from a penis. Because of the high number of Thai surgeons who are trained to perform this procedure, and its relatively low cost in Thailand, the nation has become a mecca of medical tourism for those seeking vaginoplasty, which oftentimes is not covered by insurance, Sowapark explained.

As part of the recovery process, patients must dilate two to three times per day for up to three years. Most dilators are rigid, graduated cylinders made of glass or plastic that are uncomfortable and can only be used in a private setting.

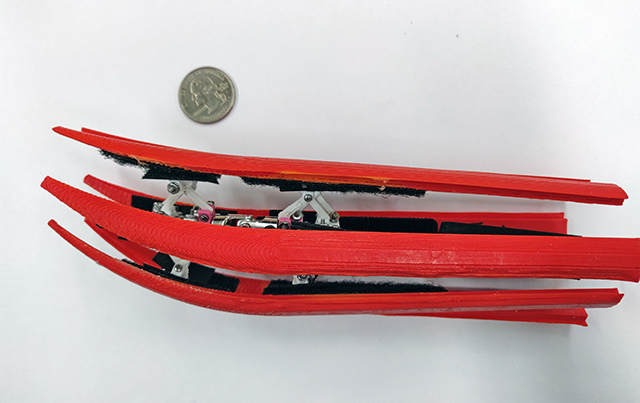

For the engineering component of her thesis, Sowapark developed a prototype for a dilator that can expand along a continuous range of diameters. Her prototype is curved, so it more easily conforms to the shape of the vagina and lower abdomen.

The dilator prototype Sowapark developed is curved, so it more easily conforms to the shape of the vagina and lower abdomen. (Photo provided by Montita Sowapark)

As a small motor gearbox rotates, a series of screws move along the shaft and push a set of arms, which are connected to the outer shell of the device to drive the expansion.

The biggest technical challenges she faced involved fabricating small parts with 3D printers, which have limitations in terms of the materials that can be used, and incorporating the best components of available dilators into a new device that met her design specifications.

But even if she had made a perfect prototype that could be implemented right away, Sowapark acknowledges she’d still be left with unanswered questions.

“The way that gender dysphoria is defined can sometimes perpetuate a reductive or flattening narrative of trans identity—that a person needs this medical service to treat gender dysphoria,” she said. “In designing this device, a potential consequence is that it furthers this narrative: ‘oh, you’re a trans woman, I know what that means, you want to have this surgery, and then you need to have the best technology in order to undergo dilation in a successful way so you don’t have complications down the line.’ I’m not sure if it is my place to be reinforcing that narrative.”

Most commonly available dilators have rigid bodies, but the prototype Sowapark developed can expand along a continuous range of diameters. (Photo provided by Montita Sowapark)

For Sowapark, who received a John Loiello AFSOAS FISH Scholarship that will help fund her graduate studies in medical anthropology in London next year, the thesis project was an invaluable learning experience, both from a technical side and theoretical point of view.

Whether or not she continues working on the device, she’ll draw on those lessons as she moves on to pursue an M.D.-Ph.D. in medical anthropology and science and technology studies, with the goal of exploring how science shapes and is shaped by social undercurrents.

“I really learned about navigating health problems and inequities in a way that can illuminate underlying, unresolved questions. We are at this moment in health care where so much has been achieved by biomedical technologies, but there are still many domains where biomedicine is struggling to solve our health problems, like mental health,” she said. “This thesis has really forced me to think about what biomedical engineering is, what it means, what it can do, what it should do, and what its limits are.”

Topics: Bioengineering, Diversity / Inclusion, Health / Medicine

Cutting-edge science delivered direct to your inbox.

Join the Harvard SEAS mailing list.

Press Contact

Adam Zewe | 617-496-5878 | azewe@seas.harvard.edu