Data scientist battles abusive behavior on Twitter

More than 336 million active Twitter users (a number slightly larger than the entire U.S. population) send hundreds of millions of tweets every single day.

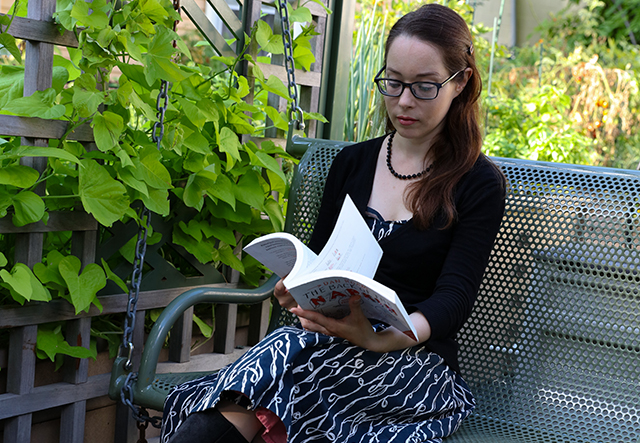

Ensuring those users contribute to a healthy conversation on Twitter is the goal of Kristen Sunter, S.M. ’06, Ph.D. ’14, a data scientist in the social media company’s applied research group. Her team uses computational techniques to root out Twitter abuse.

“I enjoy my job because I feel like I am doing good in the world by combating some of the abusive things that can happen on the internet,” she said. “It gives me an opportunity to combine my analytical skills with my interest in internet culture, and human culture more widely.”

Sunter’s journey to a data science career began with a seemingly unrelated interest in geology. An avid rock collector as a child, she fondly recalls the shimmering crystals in her favorite piece of jet-black snowflake obsidian.

That interest inspired her to pursue archaeology as an MIT undergrad, which introduced Sunter to the world of materials science. She soon changed her focus from geology to semiconducting, optical, and magnetic materials.

After earning a master’s degree in applied physics from the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS), Sunter joined the Jet Propulsion Laboratory to gain industry experience. She worked on a satellite development unit, setting up optics for testing before the devices were flown into space.

While she enjoyed the work, Sunter knew she needed a Ph.D. to advance her career, so she returned to SEAS, cross registered at MIT, and joined the lab of Karl Berggren, Professor of Electrical Engineering. As an applied physics Ph.D. candidate, she studied single photon detectors composed of superconducting nanowires.

Sunter’s thesis focused on optical modeling, using analytical equations to determine which combinations of materials were ideal when developing single photon detectors. Her work could help researchers better understand their detectors’ absorption limits.

While completing her thesis, she realized she didn’t like working in a lab as much as she enjoyed coding.

“I think I’ve always really liked the analytical aspects of science,” she said. “Coding is very clean. In experimental work, it can sometimes be very difficult to know why a given chip failed. It might be something out of your control. In coding, it is much more straightforward—when something doesn’t work, it is because there is a bug in the code.”

While Sunter’s thesis involved its share of analysis, she didn’t get much coding experience through her research. She began taking data science courses online and soon developed a full-blown passion for the discipline.

As she was beginning her hunt for a data scientist job, Sunter fell into her role at Twitter by happenstance. A friend who worked for the social network recommended her to the manager of a data science team in the Boston office, and she joined the company in 2015.

Much of Sunter’s work centers around opportunity sizing and impact analysis related to the social network’s abuse policy. For instance, Sunter examined recent changes to the witness reporting policy that give more weight to abuse reports filed on a user’s behalf by someone the user is following.

“People with a lot of followers who are involved in abusive exchanges can receive a lot of abusive content and may not have the bandwidth to report every abusive tweet,” she said. “This way, their followers are better able to help report the abusive content.”

One of the biggest challenges Sunter and her colleagues face is trying to understand problems that are very complex, and deeply mired in subjectivity and human nature.

“People use Twitter in a lot of different ways, so there is no such thing as a typical user,” she said. “Something that may be a good change for one type of person may be detrimental for other users.”

In Japan for instance, Twitter’s second biggest market, users typically have different professional and personal accounts that are kept strictly separate. Revealing that the same person holds two accounts would be considered a huge breach of privacy.

Understanding how different cultures use the platform is critical as the team tackles new challenges with a sense of urgency.

Sunter and her team work quickly and efficiently to stay one step ahead of abusive users. They are also constantly implementing new techniques, like machine learning tools, in an effort to sort massive numbers of abuse reports and weed out bogus claims filed by abusers.

Helping to make the Twitter user experience healthier for millions of people around the world offers Sunter a rewarding way to apply her data science skills.

“I enjoy the day-to-day parts of my job, but also the bigger picture of it,” she said. “I’m very thankful that I work for a company with as large an impact as Twitter. Everything I do feels like it has a chance to make a difference.”