An avid artist and dedicated physics researcher, grad student Jovana Andrejevic has found a perfect outlet for both her passions at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences. (Photo courtesy of Jovana Andrejevic)

To Jovana Andrejevic, there’s a beauty to engineering that can sometimes be better expressed with charcoal pencils and a sketchpad than with differential equations and computational models.

Andrejevic is pursuing a Ph.D. in applied physics at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, where she has found an ideal outlet for her artistic acuity and scientific savvy in the lab of Christopher Rycroft, Associate Professor of Applied Mathematics.

During her early childhood in Serbia, art and science were dueling interests for Andrejevic. She spent hours drawing with her twin sister, Nina, especially after the family moved to the Chicago suburbs when she was 7.

“My sister and I didn’t speak any English when we came to the U.S., but in a way, that brought us closer together because we were facing the same challenges at the same time,” she said. “It helped because we knew we had each other to lean on.”

Andrejevic and her twin sister, Nina, who is currently pursing a Ph.D. at MIT. (Photo courtesy of Jovana Andrejevic)

Though she and her sister had always enjoyed math and science, a particularly engaging high school physics class inspired Andrejevic to major in physics as an undergrad at Cornell University.

After only a semester, she realized she had a passion for teaching, and jumped at the opportunity to be a teaching assistant for introductory physics courses.

“My physics teacher in high school had such an approachable way of teaching the subject that it made me want to build that skill and be able to pass on that knowledge and passion the way that he did,” she said. “Through the teaching process, I also expanded the scope of my understanding, how I think about the subject and the different tools you can use to understand certain concepts.”

She took her first programming class at Cornell, and was fascinated by the power of computation and its many applications in the field of physics. She began seeking a graduate program at the intersection of physics and computation, and was drawn to the interdisciplinary research in the Rycroft lab.

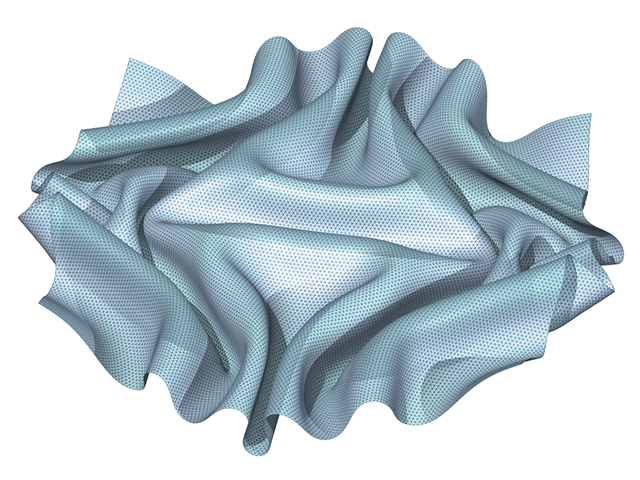

This snapshot is an example of an elastic sheet simulation from Andrejevic’s research with Chris Rycroft and collaborators. (Image courtesy of Jovana Andrejevic)

Andrejevic and her lab mates seek to understand the phenomenon of crumpling—like what happens to a sheet of paper when you crush it in the palm of your hand.

“Crumpling, you think about what we see everyday, like a crumpled sheet of paper, but the phenomenon is also observed in microscopic systems, like graphene membranes, and in something as macroscopic as the Earth’s crust,” she said. “Crumpling is an example of stress focusing in the regions of a material, as opposed to the energy spreading equally throughout the material. We want to understand what governs this stress focusing and how we can effectively predict the weak spots in a thin sheet.”

I want to continue teaching and presenting physics in a way that feels more approachable and dispels some of the initial intimidation by the subject.

Working closely with researchers in the lab of Shmuel Rubinstein, Associate Professor of Physics, Andrejevic applies machine-learning techniques to analyze data and study the statistical properties of crumpling, in an effort to elicit some sort of structure from what looks like very disordered and chaotic data.

She develops simulations of crumpling thin, deformable elastic sheets to replicate live experiments, in collaboration with experimentalist Ariel Amir, Assistant Professor of Applied Mathematics. The simulations streamline data gathering to accelerate the process of discovery.

“The topic is very interesting because we observe crumpling so often and it seems so commonplace, and yet it remains poorly understood,” she said. “Being able to understand what the failure points of a material are can help in engineering against that failure.”

One of the things Andrejevic enjoys most about the research is its visual nature; showcasing the phenomenon of crumpling through intricate and beautiful images helps communicate the science to the broader community.

She feels very passionate about using art to make science more approachable, and has found an outlet for her talents as a member of the graphic design team for Science in the News. Andrejevic creates illustrations for grad student-authored science articles, which often cover topics she is unfamiliar with, challenging her to learn about different research topics.

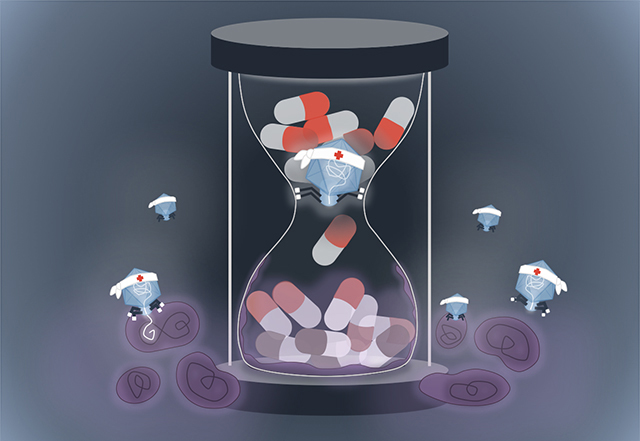

This cover photo, which features bacteriophages, was designed by Andrejevic to accompany an article written by fellow grad student Jeep Srisuknimit for Science in the News. (Image courtesy of Jovana Andrejevic)

“It can be challenging to illustrate a scientific topic. One of the things I strive to do is make an analogy with my artwork,” she said. “By making connections with things people are familiar with, it can bridge the gap between the science and their everyday lives. Art is such a great way to do that because you are able to draw clear parallels using visuals.”

She recently illustrated an article on using bacteriophages as an alternative to antibiotics. Andrejevic portrayed a bacteriophage as a comic book super hero, showing how it aids in disease prevention and treatment by fighting inside and outside the body.

Andrejevic is hard-at-work on her next drawing. (Photo courtesy of Jovana Andrejevic)

Art—whether science-related or not—is Andrejevic’s main focus outside the lab. When she’s not illustrating a science article, she can often be found drawing portraits of friends and family, making cards, or learning to play the guitar with her twin sister.

An artist’s patience, attention to detail, and creativity are the same skills she relies on as a researcher, and skills she hopes to impart to others in her future career as a physics professor.

“I want to continue teaching and presenting physics in a way that feels more approachable and dispels some of the initial intimidation by the subject,” she said.

“Even though physics is a subject that feels very rigid, there is room for creativity in how you understand it and explain it to different people."

Press Contact

Adam Zewe | 617-496-5878 | azewe@seas.harvard.edu