Water quality researcher Andrea Tokranov, an environmental science and engineering Ph.D. candidate, tracks potentially deadly contaminants. (Photo by Adam Zewe/SEAS Communications.)

Research has taken Andrea Tokranov on a journey to the surface of the moon, the depths of an ancient Indonesian lake, and the coastal communities of Cape Cod.

But her interest in science originated in the backyard of her family’s Rhode Island home. As a child, Tokranov spent as much time as possible hiking through the woods, and developed a fascination for the world around her. That passion inspired Tokranov to study geology as an undergraduate at Brown University.

“Geology teaches you a lot about processes and the way the world works,” said Tokranov, an environmental science and engineering Ph.D. candidate at the Harvard John A Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences. “It involves a lot of long-term thinking. You have to think in four dimensions: X, Y, and Z, plus the element of time.”

Tokranov’s first exposure to research involved a collaborative project with two professors who studied moon dust brought back by Apollo astronauts . They analyzed tiny, colored glass beads in the dust that were formed by ancient volcanic eruptions on the moon.

Billions of years ago, volcanoes deep inside the moon erupted, pushing gas to the surface. That gas-rich magma instantly froze at the surface, forming tiny glass beads with gases trapped inside. The colorful microscopic orbs hold clues about the moon’s formation.

Billions of years ago, volcanoes deep inside the moon erupted, pushing gas to the surface. That gas-rich magma instantly froze at the surface, forming tiny glass beads with gases trapped inside. The colorful microscopic orbs hold clues about the moon’s formation.

“While I enjoyed that project, those samples were from three billion years ago, and it was a little too far removed from modern life for me,” Tokranov said. “So I switched to paleogeology, looking at climate records to try to draw ties to today.”

For her senior thesis, Tokranov studied the sediment of an ancient lake in Indonesia, which offered an 80,000-year geological record. Analyzing the sediment provided insights into everything from weather patterns to climate indicators over a vast span of Earth’s history.

Tokranov found the research fascinating, but still felt drawn to work in an area more relevant to today. After graduating from Brown, she joined the data analysis group of an environmental consulting firm where she provided guidance on remediation projects. The experience taught her a great deal about environmental engineering and coding, but a desire to lead her own projects inspired Tokranov to pursue a Ph.D.

In the lab of Chad Vecitis, Associate Professor of Environmental Engineering, Tokranov is conducting research on a class of emerging contaminants known as poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs). While some information exists about the potential health effects of these emerging contaminants, there is not enough data for the EPA to establish enforceable regulations, she explained.

Despite their relative obscurity, PFASs are a huge class of compounds, containing more than 3,000 chemicals.

“We’ve been producing them since the 1950s, so they are all over the place, and that’s the problem,” she said. “They are in our groundwater, they are in our drinking water, they are everywhere. We used to assume these chemicals were safe because they are really stable compounds, but now we are starting to see that there are some serious health effects.”

Last year, the EPA issued a drinking water advisory for two of the most pervasive and well known compounds, PFOS and PFOA, which may cause cancer and thyroid disease, obesity, as well as damage to the immune system.

Last year, the EPA issued a drinking water advisory for two of the most pervasive and well known compounds, PFOS and PFOA, which may cause cancer and thyroid disease, obesity, as well as damage to the immune system.

By studying these compounds, which are produced by chemical manufacturers, Tokranov seeks a better understanding of how they are carried from the contamination site into ground and surface water. Armed with information on the transport processes, environmental officials can predict when and where the chemicals will cause drinking water contamination.

Working with the United States Geological Survey, Tokranov focuses on Cape Cod, where all drinking water is sourced from groundwater. Decades of PFAS infiltration from Joint Base Cape Cod military installation have increased the groundwater contamination risk in certain areas, Tokranov said.

In addition to taking and analyzing groundwater samples, Tokranov recently expanded the scope of her project to explore surface water interactions, such as how the chemicals infiltrate lakes and river systems.

While she enjoys the fieldwork, the biggest challenge she faces is that few people are aware of these chemicals, so there is little existing research to study and few potential collaborators to consult. She hopes her Ph.D. thesis not only raises awareness of these dangerous contaminants, but also provides a framework officials can use to develop solutions that improve people’s health.

“If you know the fate and transport processes, you would know what problems to predict, and you would be able to solve them. You wouldn’t have to go out and spend millions of dollars to test every single person’s well,” she said. “The rewarding part of this work is being able to help communities.”

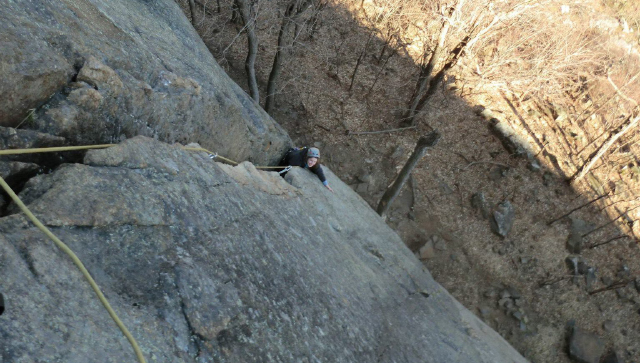

An avid rock climber, Tokranov still enjoys spending time in the outdoors. (Photo provided by Andrea Tokranov.)

Press Contact

Adam Zewe | 617-496-5878 | azewe@seas.harvard.edu