News

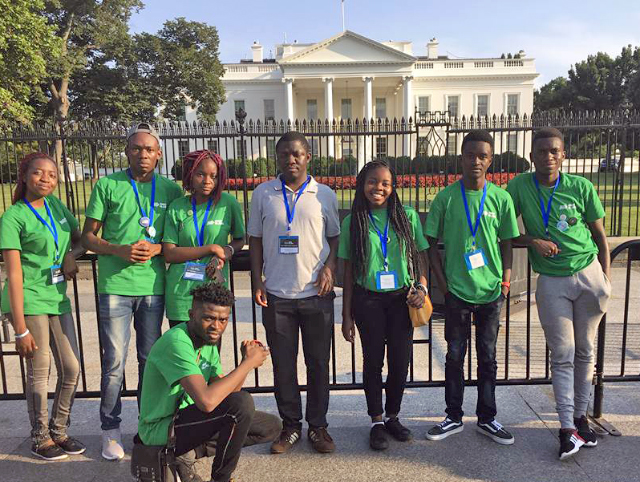

Members of the Zambian FIRST Global robotics team, launched and mentored by Harvard sophomore Sela Kasepa, at the international robotics competition in Washington, D.C. (Photo provided by Sela Kasepa.)

While channel surfing one afternoon from her living room in Kitwe, Zambia, Sela Kasepa happened upon a program about the Pan-African Robotics Challenge. Enthralled, Kasepa thought a robotics competition could inspire her fellow Zambians to take an interest in STEM, fueling technical advancement in the developing Central African nation.

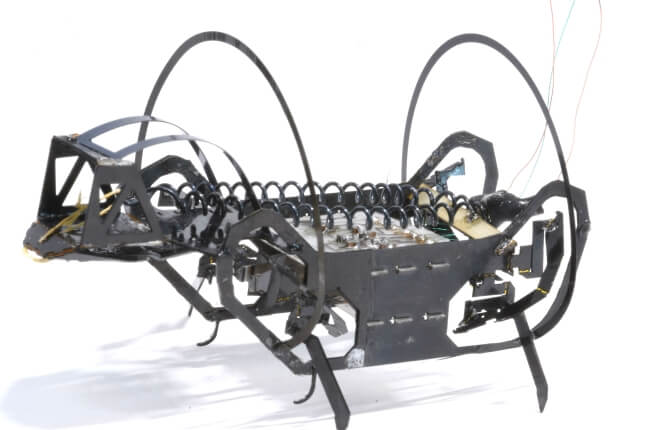

Fast forward a few years and Kasepa, now a freshman at Harvard College, was again struck by the power of robotics while building her own machine for the John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences course Computer-Aided Machine Design (ES 51). She felt empowered as the robot maneuvered around a competition course.

“Many people would say robotics is a far-fetched idea, but there is so much more involved than building a robot,” she said. “You think, ‘I have made this with my own hands, and I could make more things.’ Robotics can drive a change in mindset. If we can help young people have that feeling, that can drive technological advancement.”

Harvard sophomore Sela Kasepa, a native of Zambia, launched and mentored her country's inaugural FIRST robotics team. (Photo provided by Sela Kasepa.)

Kasepa began seeking a robotics competition that Zambian youth could join, and found FIRST Global, an annual student robotics Olympiad founded by inventor and entrepreneur Dean Kamen. Zambia was not among the 162 participating countries, so she inquired about future contests. Organizers urged her to launch a team for 2017, even though other nations had already begun raising money and training students.

“It felt like such an outside idea. I wondered if it was even possible,” she said. “I decided to take up the challenge. If you never dare to start, you probably will never end up starting at all.”

Kasepa immediately dialed her mentor, Peter Lungu, director of the Zambian Institute for Sustainable Development (ZISD), a nongovernmental educational outreach organization that had awarded her a scholarship, setting her on a path toward Harvard. Lungu agreed to help recruit students and mentor the team in Zambia, since Kasepa was now deep into her college coursework.

They enlisted seven students, set up a robotics shop at the ZISD headquarters, and ordered the FIRST Robotics kit containing materials to build the machine.

Students on the Zambian FIRST Global robotics team take a much-deserved break while working to finish construction of their robot. (Photo provided by Sela Kasepa.)

The competition theme was clean drinking water, and robots were tasked with collecting and sorting color-coded bowls signifying clean and contaminated water. While the kit included basic building guides, Kasepa coached the team via Skype and recorded demos of fabrication techniques on Youtube.

Passionate and dedicated, the students worked from sunrise to sunset as they caught up with their international competitors. Remotely, Kasepa’s encouragement boosted teammates as they hit roadblocks, like when parts broke and they lost precious time waiting for replacements to pass through customs.

“With every building process, just when you think it works, technical or design faults always develop,” she said. “The robot had to be rebuilt a number of times.”

But as the robot came together, a new worry came to the front of Kasepa’s mind—funding the journey from Zambia to the international competition in Washington, D.C. in July.

Kasepa began making cold calls, which all fell on deaf ears. Not sure where to turn, she shared her frustrations during a casual conversation with Evelyn Hu, Tarr-Coyne Professor of Applied Physics and Electrical Engineering. Hu offered to help, and secured a grant from the Office of the Vice Provost for Research that would fund travel expenses for the three team members required to qualify. Using Lungu’s contacts at an Ethiopian airline, they negotiated sharply discounted airfare and were able to fund travel for all seven teammates. Kasepa was elated, but lacking funding for herself, she would have to watch the competition streamed live online.

The members of the Zambian FIRST Global team also had the opportunity to explore the sites in Washington, D.C. (Photo provided by Sela Kasepa.)

The first match ended early for the Zambian team; one of the robot’s chains was displaced and they were unable to fix it before time ran out. Devastated, the students worked long into the night making repairs.

On the second and final day of competition, Kasepa tuned in. Wringing her hands with worry, she leaned close to the computer screen as the Zambians’ match began. As each frenzied match unfolded, her heart’s staccato pounding gradually decelerated as the robot continued operating seamlessly. When the dust settled, the nation had earned 32nd place out of 163 national teams.

“I am extremely proud of them,” she said. “I hope they learned that they are more than capable of being innovative and creating something. As a nation, Zambia needs to drive toward innovation, and these students can be leaders in that arena.”

Zambian team members are ready to compete inside the FIRST Global robotics competition arena. (Photo provided by Sela Kasepa.)

Kasepa, who also organized a robotics showcase for Zambian schoolchildren during a school holiday, wants the country’s participation in FIRST Global to continue. She is hopeful that with the support of mentors and the excitement of the young students who saw their country’s robot compete on a global stage, they will be able to sustain the program.

“It is now clear to me that a country’s greatest resource is its people,” she said. “If you have people who are willing to work toward something, I definitely think a country’s future can be bright. The minerals or raw materials in the earth are not as valuable as the ideas that people step up to achieve together.”

First Global Team Zambia 72

This video showcases the members of the Zambian FIRST Global robotics team.

Topics: Robotics

Cutting-edge science delivered direct to your inbox.

Join the Harvard SEAS mailing list.

Scientist Profiles

Evelyn Hu

Tarr-Coyne Professor of Applied Physics and of Electrical Engineering

Press Contact

Adam Zewe | 617-496-5878 | azewe@seas.harvard.edu