Seeking genuine collaboration with artificial intelligence

Popular culture sometimes paints a bleak picture of interactions between artificial intelligence and humans (think “2001: A Space Odyssey” or “Blade Runner”). Alumna Ece Kamar, Ph.D. ’10, doesn’t see it that way.

Kamar, who earned her graduate degree in computer science at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS), studies how humans and machines can work together.

“If you build an artificial intelligence system that is going to function alone, that system is not going to have any value for humans,” said Kamar, a scientist in the Adaptive Systems and Interaction Group at Microsoft Research. “Collaboration capabilities need to be studied in parallel to the work we do to build these systems. This challenge is often overlooked.”

At Microsoft Research, alumna Ece Kamar, Ph.D. '10 (computer science) studies how humans and machines can work together. (Photo provided by Ece Kamar.)

A native of Turkey, Kamar’s interest in math and science was fueled by a childhood love of jigsaw puzzles. As an undergraduate at Turkey’s prestigious Sabanci University, she found that her analytical mind and interest in languages dovetailed perfectly with the field of computer science. In her first exposure to research, she worked alongside a faculty member to build machine-learning systems aimed at improving Turkish spell-check applications.

Under the advisement of Barbara Grosz, Higgins Professor of Natural Sciences at SEAS, the Ph.D.-candidate initially planned to continue her language processing work. But as she delved deeper into the collaborative nature of language, she felt drawn to multi-faceted problems posed by human-computer interaction.

Kamar’s academic success earned her a Microsoft Research Fellowship, an award given to just a dozen U.S. graduate students each year. As a Fellow, she used machine learning and planning to develop a prototype of a collaborative ride-sharing system for Microsoft employees.

“That experience was transformative for me,” she said. “In school, I was focused on abstract problems, but during my internships at Microsoft Research, I had the chance to apply those techniques to real-world problems.”

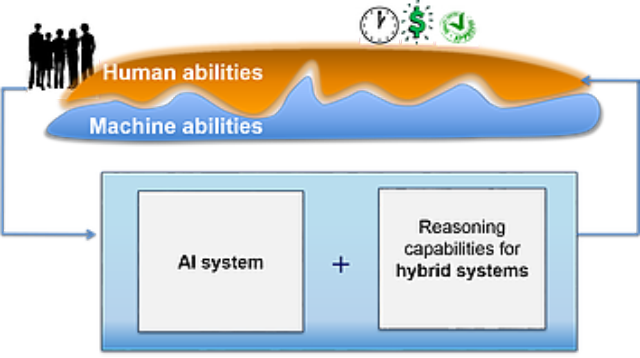

Today, Kamar is leading projects in an area she calls “hybrid intelligence,” which involves the combination of strengths and weaknesses from both human and artificial intelligence to get the most out of AI systems.

“How can we use human intelligence to understand where our AI systems are failing?” she said. “If the data we use to build the system is incomplete or biased, then all these biases and blind spots are reflected in the system, too.”

Kamar incorporates those ideas into a wide variety of applications, including AI personal assistants that can assist people with their daily lives. Systems like these must be collaborative so they can identify when users need help, and what assistance they require.

She also applies her research techniques to interactive systems, where humans and computers tackle a problem together online or in the physical world. Enhancing collaboration by enabling machines to understand human needs, strengths, and weaknesses, with their many tiny nuances, is one of the most challenging quandaries she explores.

Kamar expects interactive systems to pose some of the thorniest problems for AI researchers in the future. In an attempt to map out the implications of this rapidly growing field, she has collaborated with leading researchers in the One Hundred Year Study of Artificial Intelligence. The far-reaching, Stanford-based initiative, whose standing committee is chaired by Grosz and also includes David Parkes, George F. Colony Professor of Computer Science, explores both AI today and potential future uses of the technology.

“There is a public perception that AI is going to be moving very fast and without our control,” she said. “I am hopeful this project can help to explain AI and create awareness about opportunities and challenges, which will emphasize the importance of human-computer teamwork.”

Kamar foresees technology improvements that enable more seamless collaboration. Merging approaches that have often been pursued separately, such as knowledge representation and statistical machine learning methods, will help AI become a better resource for humans.

“Thinking about the products and the real-world impacts, and what kinds of domains and applications are going to be influential, is such a fun part of my job,” she said. “AI is going to make life better in many different areas. Being able to contribute to that line of work is rewarding.”