News

"Surf and Turf" team members Davis Wilkinson, Alana Davitt, and Sam Meijer (left to right) triumphed over their ES 51 classmates in the Turf Wars competition. (Photo by Eliza Grinnell/SEAS Communications.)

Cheers erupted from the crowd of spectators as the final seconds of the “Turf Wars” robot racing competition ticked down to zero. Alana Davitt, Sam Meijer, and Davis Wilkinson hoisted their arms into the air and applauded wildly as the reality of their victory sunk in.

For the three, students in the hands-on Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences course “Computer-Aided Machine Design” (ES 51), their victory was the culmination of a frenzied term filled with design, construction, testing, and troubleshooting.

Sam Meijer, Alana Davitt, and Davis Wilkinson (left to right) watch as their robot reaches the top of the AstroTurf ramp. (Photo by Adam Zewe/SEAS Communications.)

In fact, little more than a month before the May 4 competition, the students weren’t sure if their robot would be able to drive at all.

They were hard at work in the Active Learning Labs, anxiously waiting to use the laser cutter to add additional details to a bright yellow piece of acrylic that would form the base of the vehicle. Their objective by the end of the three-hour lab session sounded simple: show that their design could move. Frustration set in as the team realized the wheels they had crafted didn’t seem to fit the belts.

“It was crunch time and we were just stapling the belts together and screwing the wheels on with only a few seconds to spare,” recalled Davitt, S.B. ’19, a mechanical engineering concentrator. “We plugged it in and it just kept spinning in circles. We said, ‘well, it moves, but clearly we have some work to do.’"

Meijer prepares a piece of acryllic for the laser cutter. (Photo by Adam Zewe/SEAS Communications.)

Over the course of the next month, with the date of the competition looming, they spent hours refining their design.

Davitt, Meijer, and Wilkinson formed team “Surf and Turf,” one of 16 student teams charged with building a mobile robot from the ground up. The hands-on course teaches the fundamentals of mechanical design, incorporating the remote-controlled robots as a “fun vehicle” to emphasize the principles and techniques students learn in class, explained course instructor Daniela Faas, Senior Preceptor in Design Instruction.

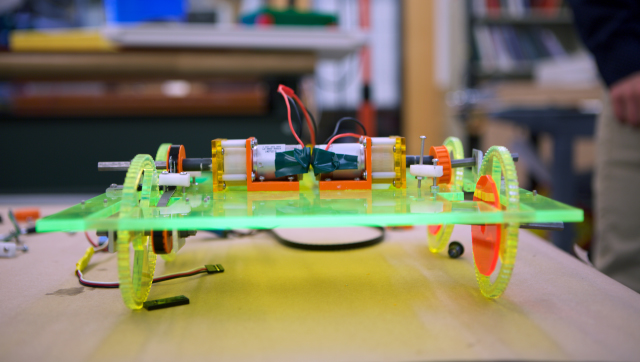

The students drew on several engineering processes and techniques while completing the project, including initial sketching and CAD modeling, materials selection, machine elements, and motor control. During the culminating competition, a race against the clock, robots earn points by driving up and down a bumpy, AstroTurf ramp, and also by picking up tennis balls and placing them onto a sticky grid.

With that final competition in mind, Davitt and her teammates let their ingenuity lead the way. Initially, they designed an ambitious robot with a claw that would rotate to carefully place tennis balls onto the grid. As the course progressed, they retooled their design and focused on developing a fast and durable machine that could effectively climb the ramp (and earn the maximum number of points).

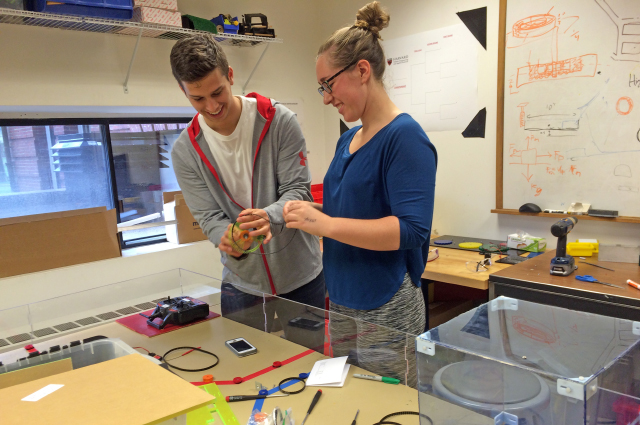

Meijer and Davitt discuss some preliminary design details. (Photo by Adam Zewe/SEAS Communications.)

Keeping an open mind helped the team achieve success, said Meijer, S.B. ’19, a mechanical engineering concentrator. One of his favorite success stories during their marathon lab sessions was the first time the robot climbed the test ramp.

“When we first started driving up the ramp, the robot kept tipping over backward, but we didn’t know yet where to attach the motor control or battery to weigh it down,” he said. “I happened to be holding a tangerine, so we just taped the fruit to the front of the robot, figuring it was about the right weight. Then it just drove up the ramp without issue.”

Group troubleshooting was a common practice during the team’s weekly lab meetings, said Wilkinson. He and Davitt often found themselves reining in Meijer’s big ideas (always diplomatically, of course). But the teammates, who hadn’t met before the class, developed strong friendships as they learned to use an array of mechanical equipment and computer programs.

“Effective teamwork was really the biggest contributor to our success,” said Wilkinson, A.B. ’17, a joint concentrator in economics and computer science. “We meshed well, we communicated well, and we each brought different strengths to the table.”

Wilkinson and Davitt collaborate to fit the belts to their machine's wheels. (Photo by Adam Zewe/SEAS Communications.)

That’s not to say they didn’t make mistakes along the way. Meijer recalled an instance where the team used one sixth of their entire acrylic stock producing a chassis that they almost immediately realized was far too narrow. The lesson they learned from that nearly disastrous mistake—take it slow and measure everything first.

In addition to learning about the tools of engineering , the term-long project instilled in the three students a greater appreciation for all that is involved in the design process.

“I came in with very little engineering or design experience, so it really helped me to build confidence and realize I can succeed in this field,” said Davitt. “Even though I spent a ton of time in the lab, I really enjoyed every hour.”

Meijer said one of the most significant lessons he gleaned from this course came from the team’s many trial-and-error moments.

“If you break a complex problem down into small enough parts, it becomes instantly solvable,” he said.

Team Surf and Turf's finished machine is a force to be reckoned with. (Photo by Adam Zewe/SEAS Communications.)

Though Wilkinson will not be pursuing an engineering career, he felt right at home in the lab with his classmates. The course left him with invaluable problem-solving experience.

“Working together as a team to solve problems has been really satisfying,” he said. “This course really impressed upon me how much fun it is to build something.

Helping students to develop confidence in their abilities as designers and builders is the primary aim of ES 51, Faas said. Many students who take the course are freshmen or sophomores with no prior manufacturing experience.

“My goal is to enable students to become learners and be confident in their ability to approach problems. Most entering students feel comfortable with basic scientific theory, for example, but have never solved a knotty design puzzle,” she said. “My ambition is that everybody can have a positive experience in ES 51 and not be limited by their background or incoming abilities.”

Turf Wars 2016

Watch team Surf and Turf's robot outrun its opponent in the final round of the ES 51 Turf Wars competition at the SEAS Design and Project Fair. (Video by Eliza Grinnell/SEAS Communications.)

Cutting-edge science delivered direct to your inbox.

Join the Harvard SEAS mailing list.

Press Contact

Adam Zewe | 617-496-5878 | azewe@seas.harvard.edu