News

Students trek through the Amazon rainforest during a field program in Peru.

Green and lush, the Amazonian rainforest of Peru’s Madre de Dios region envelops the team of students and faculty as they trek through the thick underbrush.

Ahead, a clearing reveals the stark contrast of this remote region – ugly mounds of earth are scattered across a clear-cut patch of what was once pristine rainforest. Rivulets of tainted, muddy water flow into the nearby river, giving the water a dull, orange hue.

This is precisely the devastation that these Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences students and faculty members have come to see. They traveled to the rainforest for a two-week field program during which the students collaborated with Peruvian peers to develop equipment that could be used by local villagers to filter the contaminated water.

This devastation in the Peruvian rainforest is caused by illegal gold mining.

Illegal gold mining is to blame for the scene the team witnessed in the rainforest. Miners scoop up river sediment, mix it with mercury to extract the gold, and then leave the contaminated soil behind, explained Chad Vecitis, Associate Professor Environmental Engineering. Vecitis and Joost Vlassak, Abbott and James Lawrence Professor of Materials Engineering, served as faculty advisors for the field program.

“In the U.S., you can buy a water filter from the grocery store that will remove the mercury and other toxins from the water, but people living in these remote regions don’t have that luxury,” Vlassak said.

The Harvard students, Cameron Akker, S.B. ’18, an electrical engineering concentrator, Forrest Lewis, A.B. ’17, an earth and planetary sciences and environmental science and public policy concentrator, Jenny Horing, S.B. ’18, a mechanical engineering concentrator, John Rahill, S.B. ’18, an environmental science and engineering concentrator, Eboni White, S.B. ’17, a mechanical engineering concentrator, and Yankang Yang, S.B. ’18, an electrical engineering concentrator, collaborated with six students from the University of Engineering and Technology (UTEC) in Lima, Peru’s capital, during the field program.

The students gathered water samples to test for pollution.

The students gathered water samples from the contaminated sites to test for pollution. Then, back in Lima, they divided into three teams to develop different projects aimed at cleaning the polluted water.

“People who live in this remote region don’t understand the harm the illegal mining is doing,” said Rahill. “If they see clear water, they assume that it is clean, but just because you filter out the larger particles doesn’t mean it is safe to drink.”

In an effort to help provide safer drinking water for the locals, the students developed a water filter that used cilantro to remove toxins, a turbine-driven centrifuge to remove large particulates, and an electromagnetic filtration system.

Horing’s team used PVC pipe, activated carbon, sand, and small pieces of copper and steel to create the electromagnetic water filter. Water trickles through a layer of activated carbon that separates the heavy metal ions, which then stick to copper and steel plates when a current runs through the system.

“We wanted our projects to be something that the people living there could make, so we tried to use the cheapest and most readily available materials we could find,” she said.

Back at the UTEC lab in Lima, the students tested the water samples to determine which pollutants were present.

For their water filter, White and her teammates used a material that grows in abundance throughout the region: cilantro. Filtering contaminated water through a layer of dried cilantro actually proved to be very effective at removing lead, White said. The filter, made from PVC pipe, was also unique because it incorporated a flip-flop as a pump and a layer of t-shirts to strain out larger particulates.

“I was very impressed by how effective our simple design was,” White said. “We oftentimes forget that, in this age of technology, a piece of equipment doesn’t have to cost thousands of dollars to work.”

The third student team worked to build a centrifuge powered by a turbine that utilized the natural flow of the river to operate. The spinning centrifuge would separate sediment from the clean water, which could then be collected, explained Lewis.

“This was such a great opportunity to really feel like there was purpose behind our work,” Lewis said. “We felt a strong level of commitment to our project because we knew that what we were developing could have concrete effects on the community.”

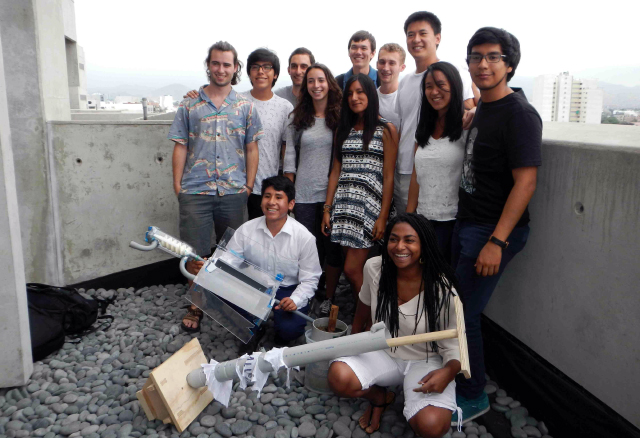

The Harvard and UTEC students collaborated to develop two water filters and a turbine-powered centrifuge.

Over the next few months, the Peruvian students will continue to work on the prototypes that were developed during the field program. They are planning a trip to Harvard this summer, where they will continue to improve the devices with their peers at SEAS.

Though their time in Peru was short, Vlassak and Vecitis hope the students returned with a deeper sense of how engineering can be used to solve real-world problems.

“People are suffering and dying because of this problem. With a little ingenuity, you can make a huge difference,” Vlassak said. “Hopefully, this will inspire our students to tackle problems that have real impacts on people’s lives.”

Cutting-edge science delivered direct to your inbox.

Join the Harvard SEAS mailing list.

Press Contact

Adam Zewe | 617-496-5878 | azewe@seas.harvard.edu