Special delivery: alumna’s startup puts essential technologies into the hands of those who need them most

As she hitchhiked her way across sub-Saharan Africa, Jackie Stenson found herself feeling more and more frustrated.

The 2008 graduate of the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences was on a personal quest to learn about sustainable, life-improving technologies and to launch a career in social entrepreneurship. As she traveled from village to village, she came across plenty of bicycle ambulances and water pumps, but almost all were broken, unusable, or forgotten by the villagers they were intended to help. In neighboring villages, people had no idea those products even existed.

Stenson (right) and Essmart co-founder Diana Jue stand inside a crowded mom and pop shop. (Photo provided by Jackie Stenson.)

Stenson’s frustration reached a boiling point when she picked up the UNICEF report, “An Appropriate Technology Round Table Discussion,” while traveling through Malawi, one of the world’s least-developed countries. The book detailed numerous life-improving technology products already on the market, from low-cost water pumps to bicycle-powered machines. It had been published in 1983.

“Why can you get a Coca-Cola in even the tiniest villages in Africa and India, but you can’t get an improved cook stove, or a solar lantern, or a water filter?” she asked. “There was this big disconnect between the engineers who were designing these products and the people living in remote villages for whom the products are created.”

After earning a master’s degree in technology dissemination strategies, Stenson, an engineering sciences concentrator, returned to Cambridge, where she crossed paths with Diana Jue, an MIT alumna who was studying sustainable dissemination channels. The two compared notes, put their heads together, and started a company to tackle the distribution problems they had encountered firsthand.

In the fall of 2012, they launched Essmart, a distribution company aimed at connecting villagers living in developing countries and the sustainable technology products that could greatly improve their lives. They targeted India, a nation where $500 billion in consumer spending (90 percent of the total) occurs in mom and pop shops spread throughout 50,000 tiny villages.

Motorbike-riding sales executives, based at Essmart distribution centers, travel to villages in the countryside, building relationships with shop owners and educating them about life-improving tech products. The sales representatives help shop owners identify and sell products to local villagers, and also provide service for the products if they break or malfunction.

Essmart sales representatives provide product demonstrations in a busy marketplace. (Photo provided by Jackie Stenson.)

“Our business model is a bit like the Sears and Roebuck catalog from the 1800s meets Ace Hardware’s branding of independent shops,” Stenson said. “It is very boots-on-the-ground. We’re building the infrastructure needed to get these products out to people who need them.”

India’s robust culture of local innovation enables the firm to sell more than 70 different types of sustainable development products without the need to import anything. The company operates six distribution centers throughout southern India and has reached more than 1,000 mom and pop shops. The products—ranging from solar lanterns to inexpensive farming tools—have impacted nearly 50,000 people.

Stenson, Jue, and their team of about 40 employees consistently evaluate new products, testing prototypes in local shops to determine the potential demand and ideal price point. They often hear directly from villagers about new product ideas.

The firm’s fast expansion in India showcases the need for improved distribution channels, Stenson said. As she and Jue look to expand Essmart throughout the developing world, their biggest challenge is fundraising.

“Distribution isn’t a sexy problem. It’s not something you can package up into a box and show how pretty it is. It’s a supply chain problem and an infrastructure problem, so it’s a little more intangible,” she said.

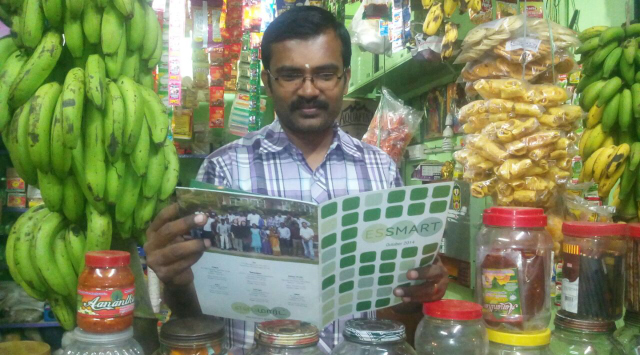

A shop owner browses the Essmart catalogue. (Photo provided by Jackie Stenson.)

In addition to helping individual villagers, Stenson envisions Essmart as a resource for engineers and manufacturers. The company is uniquely positioned to gather invaluable insights on the life-improving products villagers would be most likely to purchase and use. They currently leverage their shop network to conduct market research for engineers designing products for rural India.

Stenson, who relocated to Bangalore in 2014, has seen firsthand how simple products can have a huge impact, like a water filter that improves the health of children and a solar lantern that enables a sari weaver to earn a living wage.

“Just because you live in a village doesn’t mean you don’t deserve the same high-quality, life-improving products that other people deserve,” she said. “Being able to provide people with that choice and that dignity, to be able to tell us what they want, that’s really satisfying for me.”