News

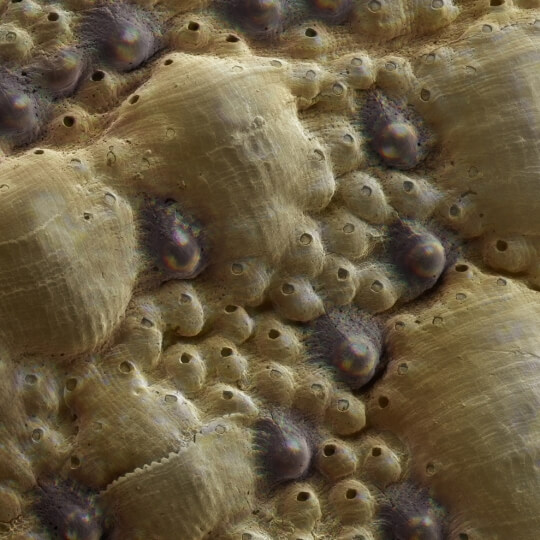

This light micrograph shows a region of the chiton’s shell surface with multiple small dark-pigmented eyes composed of aragonite, the same biomineral that also makes up the rest of the shell. (Image/SEAS and Wyss Institute at Harvard University)

Multifunctional materials with sensory capabilities like those of vision, touch or even smell could profoundly expand the possibilities of industrial design in many areas. Taking a cue from nature, a cross-institutional collaboration involving researchers from the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS), the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University and MIT have deciphered how the biomineral making up the body armor of a chiton mollusk has evolved to create functional eyes embedded in the animal’s protective shell. The findings could help determine so far still elusive rules for generating man-made multifunctional materials and are reported in the November 20 issue of Science.

Multifunctional materials that can sense physical stimuli in their environments could enable us to build houses that make use of their environments, to constantly monitor wear-and-tear and look for signs of damage in materials or even to better deliver some drugs and produce bioengineered organs.

“To date, artificial materials that have the ability to perform multiple and often structurally opposite functions are not available. We can not yet rationally design them but studying different multifunctional biomaterials present in nature should ultimately allow us to deduct the key principles for this relatively new area of materials science,” said Joanna Aizenberg, the Amy Smith Berylson Professor of Materials Science at SEAS and Core Faculty member at the Wyss Institute. Early work by Aizenberg on a sea-dwelling brittlestar that uses the same mineralized material to grow both a skeleton and visual organs had set the stage for the exploration into multifunctional biomaterials.

Now, inspired by previous biological research performed by Daniel Speiser, Aizenberg and Christine Ortiz, the Morris Cohen Professor of Materials Science and Engineering at MIT, formed a multi-disciplinary team to study another tell tale example offered by nature: the outer protective shell of the chiton Acanthopleura granulata, a tropical sea water mollusk, that is endowed with hundreds of tiny eyes. Speiser is a Professor at the University of South Carolina who joined the Harvard/MIT-led effort.

Most eyes in nature are made of organic molecules. In contrast, the chiton’s eyes are inorganic and made of the same crystalline mineral called aragonite that also assembles the body armor. They enable the chiton to perceive changes in light and thus to respond to approaching predators by tightening their grip to surfaces under water.

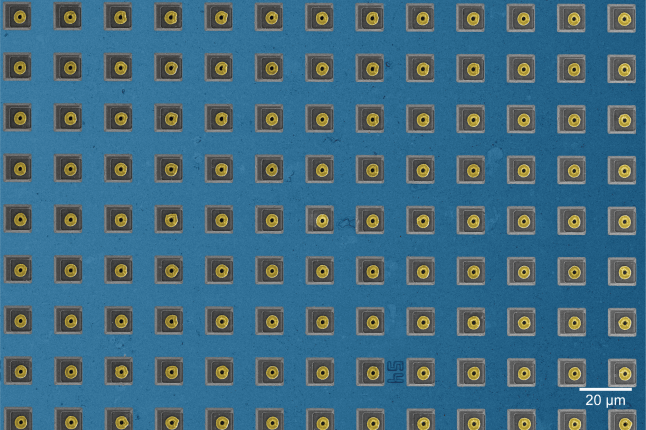

Using a suite of highly resolving microscopic and crystallographic techniques, the team unraveled the 3-dimensional architecture and geometry of the eyes, complete with an outer cornea, a lens and an underlying chamber that houses the photoreceptive cells necessary to feed focused images to the chiton’s nervous system. Importantly, the researchers found that aragonite crystals in the lens are larger than in the shell and organized into more regular alignments that allow light to be gathered and bundled.

“By studying isolated eyes, we identified how exactly the lens material generates a defined focal point within the chamber which, like a retina, can render images of objects such as predatory fish,” said Ling Li, a postdoctoral fellow working with Aizenberg and a co-first author of the study.

“We also learned that optical performance was developed as a second function to the otherwise protective shell with mutual trade-offs in both functionalities. The material properties that are favored for optical performance are usually not favored for mechanical robustness so that the evolving chiton had to balance out its mechanical vulnerabilities by limiting the size of the eyes and placing them in regions protected by strong protrusions,” said Li.

“The investigation of Nature’s finest “multitasking artists” can provide insight into functional synergies and trade-offs in multifunctional materials and guide us in other studies toward the development of revolutionary biomimetic materials. We thus are probably one step closer to construct houses made of a material that is not only mechanically robust, but also furnished with lenses capable of flexibly regulating light and temperature inside and sense environmental conditions,” said Aizenberg.

Topics: Bioengineering

Cutting-edge science delivered direct to your inbox.

Join the Harvard SEAS mailing list.

Scientist Profiles

Joanna Aizenberg

Amy Smith Berylson Professor of Materials Science and Professor of Chemistry & Chemical Biology

Press Contact

Leah Burrows | 617-496-1351 | lburrows@seas.harvard.edu