News

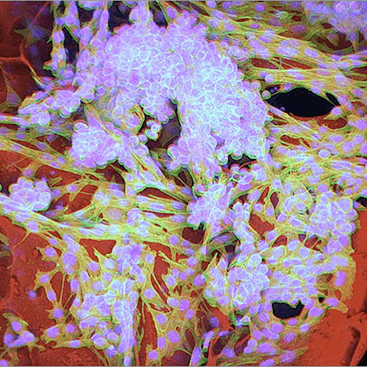

Cancerous melanoma cells shown with their cell bodies (green) and nuclei (blue) are nestled in tiny hollow lumens within the polymeric cryogel (red) structure. Credits: Thomas Ferrante, Sidi A. Bencherif / Wyss Institute at Harvard University

New Harvard research could potentially yield a new platform for cancer vaccines. Leveraging a biologically inspired sponge-like gel called "cryogel" as an injectable biomaterial, the vaccine delivers patient-specific tumor cells together with immune-stimulating biomolecules to enhance the body’s attack against cancer. The approach, a so-called "injectable cryogel whole-cell cancer vaccine," is reported online in Nature Communications on August 12.

David Mooney, the Robert P. Pinkas Family Professor of Bioengineering at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Science, led the research in collaboration with scientists at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. Mooney is also a core faculty memeber of the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University.

His team’s latest approach differs from other cancer cell transplantation therapies — which harvest tumor cells and then genetically engineer them to trigger immune responses once they are transplanted back into the patient’s body — in that the new cryogel vaccine’s properties are used to evoke the immune response in a far simpler and more economical way.

Cryogels are a type of hydrogel made up of cross-linked hydrophilic polymer chains that can hold up to 99 percent water. They are created by freezing a solution of the polymer that is in the process of gelling. When thawed back again to room temperature, the substance turns into a highly interconnected pore-containing hydrogel, which is similar in composition to bodily soft tissues in terms of their water content, structure, and mechanics. By adjusting their shape, physical properties, and chemical composition, Mooney’s team generated sponge-like, porous cryogels that can be infused with living cells, biological molecules or drugs for a variety of potential therapeutic applications including cancer immunotherapy.

"Instead of genetically engineering the cancer cells to influence the behavior of immune cells, we use immune-stimulating chemicals or biological molecules inserted alongside harvested cancer cells in the porous, sponge-like spaces of the cryogel vaccine," said Mooney.

The cryogels can be delivered in a minimally invasive manner due to their extreme flexibility and resilience, enabling them to be compressed to a fraction of their size and injected underneath the skin via a surgical needle. Once injected, they quickly bounce back to their original dimensions to do their job.

"After injection into the body, the cryogels can release their immune-enhancing factors in a highly controlled fashion to recruit specialized immune cells which then make contact and read unique signatures off the patient’s tumor cells, also contained in the cryogels. This has two consequences: immune cells become primed to mount a robust and destructive response against patient-specific tumor tissue and the immune tolerance developing within the tumor microenvironment is broken," said Sidi Bencherif, the study’s co-first author and a research associate in Mooney’s research group.

In experimental animal models on melanoma tumors, results show that utilizing the cryogel to deliver whole cells and drugs triggers a dramatic immune response that can shrink tumors and even prophylactically protect animals from tumor growth. With the pre-clinical success of the new cancer cell vaccination technology, Mooney and his team are going to explore how this cryogel-based method could be more broadly useful to treat a number of different cancer types.

Topics: Bioengineering

Cutting-edge science delivered direct to your inbox.

Join the Harvard SEAS mailing list.