News

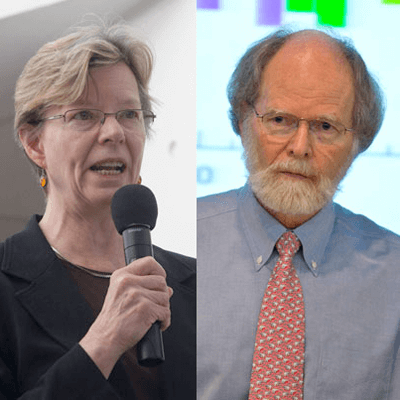

When government ponders helpful policies, Harvard faculty members are front and center. Cherry Murray (left), dean of the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, sits on the Secretary of Energy Advisory Board; and Professor James McCarthy (right) chairs the board of directors for the Union of Concerned Scientists.(File photos by Jon Chase, Justin Ide/Harvard Staff Photographers)

When Daniel Schrag arrived at Harvard as a 30-year-old geologist interested in paleoclimate, the study of climate changes through history, he didn’t realize his career was about to gain another dimension.

“My first day at Harvard, in August 1997, [Professor] John Holdren … walked down the hall and said, ‘Dan, President Clinton … has just asked me to brief each cabinet member individually before the cabinetwide discussion of what we should do about Kyoto [where an international agreement was reached to reduce greenhouse gases]. … What is new about climate science that you can tell me, that I could use to help educate the cabinet?” said Schrag, who now is the Sturgis Hooper Professor of Geology and director of the Harvard University Center for the Environment. “For me, that was ‘Welcome to Harvard.’”

When it comes to the closely linked issues surrounding climate change, energy, and the environment, Harvard faculty research regularly grabs headlines (such as January’s battery breakthrough by Sykes Professor of Materials and Energy Technologies Michael Aziz), as do efforts by the University itself to become more sustainable (such as the dozens of LEED-certified green buildings and the biomass-generating facility recently opened at the Harvard Forest). But for Schrag and many other faculty members, advising policymakers — through boards, testimony to Congress, and phone calls fielded in off-hours — is a significant, though unheralded, part of their jobs.

The demands of these advisory roles can be sizable, requiring regular trips to Washington, D.C., travel to meetings overseas, and conference calls and video conferences, as well as the research, writing, and staff time required to prepare reports and official documents.

Such advisory work can take other forms as well. For some, such as Archibald Cox Professor of Law and Director of Harvard Law School’s Environmental Law Program Jody Freeman, who worked in the White House for two years as counselor for energy and climate change, it means taking leave from Harvard to serve in an official capacity. For others, such as Albert Pratt Professor of Business and Government Robert Stavins and Raymond Plank Professor of Global Energy Policy William Hogan, it means heading advisory programs at the University, such as Stavins’ Harvard Project on Climate Agreements and Hogan’s Harvard Electricity Policy Group.

Similarly, William Clark, the Harvey Brooks Professor of International Science, Public Policy, and Human Development, co-directs Harvard Kennedy School’s (HKS) Sustainability Science Program, which supports policy-relevant studies and seeks to bridge the research and policy world on issues related to environmental sustainability. John and Natty McArthur University Professor Rebecca Henderson, meanwhile, provides a similar bridge to the business community through Harvard Business School’s (HBS) Initiative for Business and Environment, which she co-chairs.

“Harvard’s faculty members bring an enormous range and depth of intellectual power to the fields of energy and the environment,” said Richard D. McCullough, vice provost for research and SEAS professor of materials science and engineering. “Their strong commitment to meeting the challenge of climate change is evident in the work that they do to inform the development of law and policy to advance sustainability and address climate change around the world.”

Read the entire article in the Harvard Gazette

Topics: Environment, Climate

Cutting-edge science delivered direct to your inbox.

Join the Harvard SEAS mailing list.

Scientist Profiles

Michael J. Aziz

Gene and Tracy Sykes Professor of Materials and Energy Technologies