News

Ryan P. Adams, assistant professor of computer science at SEAS, contributed to a joint UCLA-Harvard study that analyses the cells in pleural fluid for signs of malignancy. "We’d like to have a system that can very rapidly detect whether or not someone has cancer," Adams said. (Photo by Eliza Grinnell, SEAS Communications.)

A team of researchers from Harvard University and the University of California, Los Angeles, have demonstrated a technique that, by measuring the physical properties of individual cells in body fluids, can diagnose cancer with a high degree of accuracy.

The technique, which uses a deformability cytometer to analyze individual cells, could reduce the need for more cumbersome diagnostic procedures and the associated costs, while improving accuracy over current methods. The initial clinical study, which analyzed pleural fluid samples from more than 100 patients, was published in the current issue of the peer-reviewed journal Science Translational Medicine.

Pleural fluid, a natural lubricant of the lungs as they expand and contract during breathing, is normally present in spaces surrounding the lungs. Medical conditions such as pneumonia, congestive heart failure, and cancer can cause an abnormally large buildup of the fluid, which is called a pleural effusion.

When cytopathologists screen for cancer in pleural effusions, they perform a visual analysis of prepared cells extracted from the fluid. Preparing cells for this analysis can involve complicated and time-consuming dyeing or molecular labeling, and the tests often do not definitively determine the presence of tumor cells. As a result, additional costly tests often are required.

The method used to assess the cells in the UCLA–Harvard study, developed previously by the UCLA researchers, requires little sample preparation, relying instead on the imaging of cells as they flow through microscale fluid conduits.

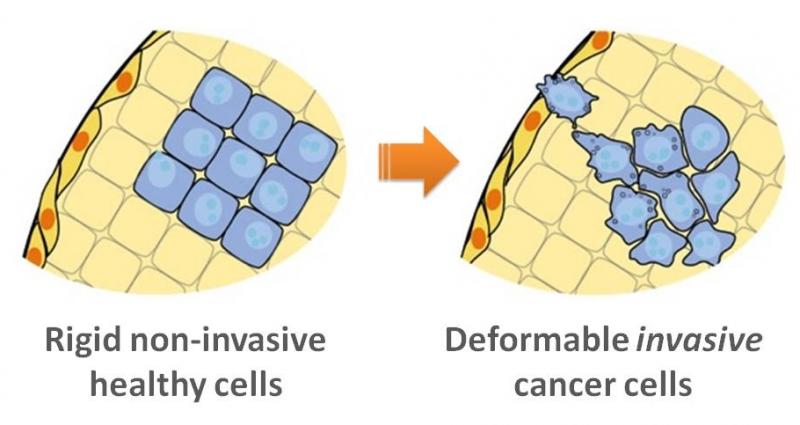

Imagine squeezing two balloons, one filled with water and one filled with honey. The balloons would feel different and would deform differently in your grip. The researchers used this principle on the cellular level by using a fluid grip to "squeeze" individual cells that are 10,000 times smaller than balloons—a technique called "deformability cytometry." The extent of a cell’s compression can provide insights about the cell's makeup or structure, such as the elasticity of its membrane or the resistance to flow of the DNA or proteins inside it. Cancer cells have a different architecture and are softer than healthy cells; as a result, they "deform" differently.

Using deformability cytometry, researchers can analyze more than 1,000 cells per second as they are suspended in a flowing fluid, providing significantly more detail on the variations within each patient's sample than could be detected using previous physical analysis techniques. Skillfully manipulating this large amount of cellular data, coauthors Ryan Adams, assistant professor of computer science at the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, and Harvard undergraduate Yo Sup (Joseph) Moon connected how the distribution of individual cells’ properties correlate with a cancer diagnosis.

The researchers also noted that the more detailed information they obtained improved the sensitivity of the test: Some patient samples that were not identified as cancerous via traditional methods were found to be so through deformability cytometry. These results were verified six months later.

The extent of a cell’s compression can provide insights about the cell's makeup or structure, such as the elasticity of its membrane or the resistance to flow of the DNA or proteins inside it. Cancer cells have a different architecture and are softer than healthy cells; as a result, they "deform" differently. (Image courtesy of UCLA.)

"Building off of these results, we are starting studies with many more patients to determine if this could be a cost-effective diagnostic tool and provide even more detailed information about cancer origin," said Dino Di Carlo, associate professor of bioengineering at the UCLA Henry Samueli School of Engineering and Applied Science and a co-principal investigator on the research. "It could help to reduce laboratory workload and accelerate diagnosis, as well as offer doctors a new way to improve clinical decision making."

Jianyu Rao, professor of pathology and laboratory medicine at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and the other co-principal investigator on the research, said the technique could potentially be used in a number of clinical settings to help manage cancer patients.

"First, it may increase diagnostic accuracy for the detection of cancer cells in body fluid samples," Rao said. "Second, it may provide a method of initial screening for cancer in body fluid samples in places with limited resources or a lack of experienced cytologists. Third, it may provide a test to determine the drug sensitivity of cancer cells."

Rao added that additional large-scale clinical studies are needed to further validate this technique for each of those applications.

Moon is now a research assistant at Harvard School of Public Health. Di Carlo and Rao are members of the UCLA Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center, and of the California NanoSystems Institute at UCLA. The paper's lead author was Henry TK Tse, a postdoctoral scholar in bioengineering at UCLA. Other coauthors included Daniel R. Gossett and Mahdokht Masaeli of UCLA's department of bioengineering; and Dr. Marie Sohsman, Yong Ying and Dr. Kimberly Mislick of UCLA's department of pathology and laboratory medicine. The research was supported by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency and the Packard Foundation.

Topics: Computer Science, Bioengineering, AI / Machine Learning

Cutting-edge science delivered direct to your inbox.

Join the Harvard SEAS mailing list.

Press Contact

Caroline Perry