News

Harvard researchers have designed a new kind of adaptive material with tunable transparency and wettability features inspired by dynamic, self-restoring systems in nature. (Image courtesy of Xi Yao.)

Cambridge, Mass. - April 8, 2013 - Imagine a tent that blocks light on a dry and sunny day, and becomes transparent and water-repellent on a dim, rainy day. Or highly precise, self-adjusting contact lenses that also clean themselves. Or pipelines that can optimize the rate of flow depending on the volume of fluid coming through them and the environmental conditions outside.

A team of researchers at the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) and the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard have just moved these enticing notions much closer to reality by designing a new kind of adaptive material with tunable transparency and wettability features, as reported yesterday in the online version of Nature Materials.

“The beauty of this system is that it’s adaptive and multifunctional,” said senior author Joanna Aizenberg, who is Amy Smith Berylson Professor of Materials Science at Harvard SEAS and a Core Faculty member at the Wyss Institute.

The new material was inspired by dynamic, self-restoring systems in nature, such as the liquid film that coats your eyes. Individual tears join up to form a dynamic liquid film with an obviously significant optical function that maintains clarity, while keeping the eye moist, protecting it against dust and bacteria, and helping to transport away any wastes—doing all of this and more in literally the blink of an eye.

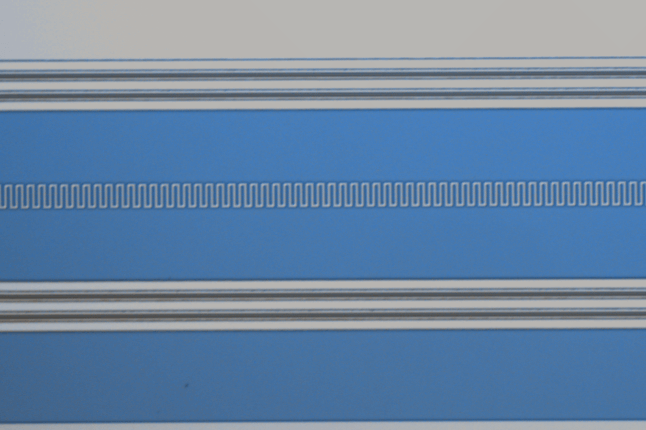

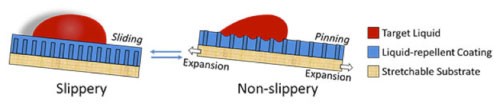

The bioinspired material is a continuous liquid film that coats, and is infused in, an elastic porous substrate—which is what makes it so versatile. It is based on a core concept: any deformation of the substrate, such as stretching, poking, or swelling, changes the size of the pores, which causes the liquid surface to change its shape.

With this design architecture in place, the team has thus far demonstrated the ability to dynamically control—with great precision—two key functions: transparency and wettability, said lead author Xi Yao, a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard SEAS and at the Wyss Institute.

Sitting at rest, the material is smooth, clear and flat; droplets of water or oil on its surface flow freely off of the material. Stretching the material makes the fluid surface rougher, Yao explained. The rough surface makes it opaque for one thing, and enables one to do something never possible before: It offers the ability to make every droplet of oil or water that is placed on it reversibly start and stop in their tracks. This capability is far superior to the “switchable wettability” of other adaptive materials that exist today, Yao said, which simply switch between two states—from hydrophobic (water-hating) to hydrophilic (water-loving).

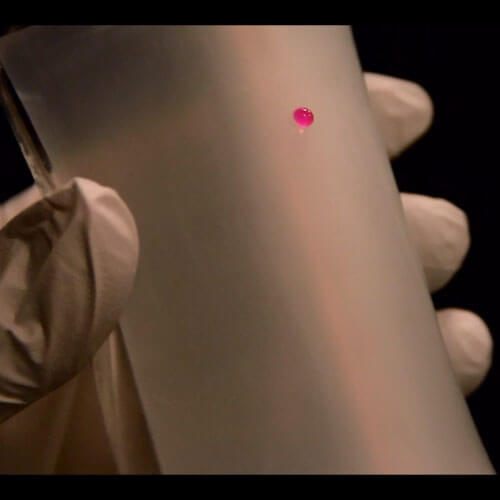

When stretched, the new material confers the ability to reversibly “pin” droplets of water, stopping them in their tracks. (Image courtesy of Xi Yao.)

“In addition to transparency and wettability, we can fine-tune basically anything that would respond to a change in surface topography, such as adhesive or anti-fouling behavior,” Yao said. They can also design the porous elastic solid such that it responds dynamically to temperature, light, magnetic or electric fields, chemical signals, pressure, or other environmental conditions, he said.

The material is a next generation of a materials platform that Aizenberg pioneered a few years ago called SLIPS (Slippery Liquid-Infused Porous Surfaces). SLIPS is a coating that repels just about anything with which it comes into contact—from oil to water and blood.

But whereas SLIPS is a liquid-infused rigid porous surface, “the new material is a liquid-infused elastic porous surface, which is what allows for the fine control over so many adaptive responses above and beyond its ability to repel a wide range of substances. A whole range of surface properties can now be tuned, or switched on and off on demand, through stimulus-induced deformation of the elastic material,” Aizenberg said.

The researchers anticipate that the new material could find applications in a diverse range of industries, including oil and gas pipelines, microfluidic and optical systems, building construction, and textiles.

In addition to Yao and Aizenberg, the paper’s coauthors included L. Mahadevan, who is the Lola England de Valpine Professor of Applied Mathematics at Harvard SEAS, Professor of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology and Professor of Physics at Harvard, and a Core Faculty Member at the Wyss Institute; Yuhang Hu, a postdoctoral fellow at SEAS and the Wyss Institute; Alison Grinthal, a staff scientist at SEAS; and Tak-Sing Wong, formerly a postdoctoral fellow at the Wyss Institute and now an Assistant Professor at The Pennsylvania State University.

The work was supported by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (AFOSR), the Office of Naval Research (ONR) and the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University.

Adapted from an original press release by the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard. Videos are available upon request.

Topics: Materials, Bioengineering

Cutting-edge science delivered direct to your inbox.

Join the Harvard SEAS mailing list.

Scientist Profiles

Joanna Aizenberg

Amy Smith Berylson Professor of Materials Science and Professor of Chemistry & Chemical Biology

Press Contact

Caroline Perry