News

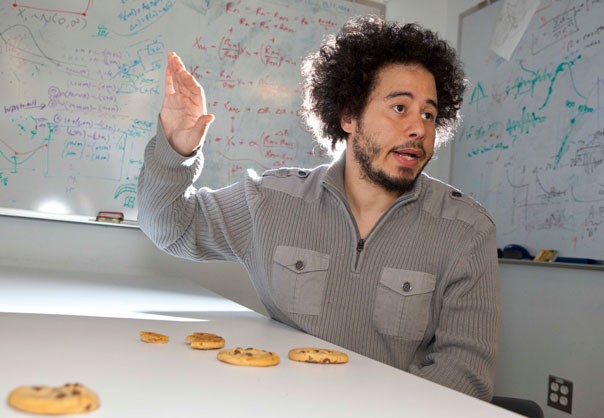

Precise movements like picking up a small object can be difficult for people with neurodegenerative diseases. Maurice Smith wants to fix that. (Photos by Eliza Grinnell, SEAS Communications.)

“When you grab a cookie and want to break off a piece with a chocolate chip,” says Maurice Smith, balancing a crumbly bit between two of his fingers, “your brain must represent that action plan extrinsically, as it is an activity based in the world.”

The cookies are on hand to celebrate the bioengineer’s birthday in his lab at 60 Oxford Street, a white squat building located on the northernmost edge of the Harvard campus. A half moon of chocolate cake with a line of colored candles still intact also sits nearby.

Gesticulating with the cookie, Smith, Associate Professor of Bioengineering at the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS), further teases out the intricacies of motor memory.

“An intrinsic representation is one that’s body-based and procedural. It relates to the complex series of muscle and joint movements your body has to make to complete a task,” Smith says.

“When I first had the thought to grab the cookie and rip off a chunk with a chocolate chip, my body responded appropriately,” he notes.

Understanding the way the brain represents extrinsic and intrinsic actions, and the relationship between the two, has been of great interest to researchers who seek to understand motor control and motor learning—or, put simply, how we learn to move.

Just a few months ago, Smith and his colleagues in the Neuromotor Control Lab laid out a generalizable theory about how the brain encodes such motor memories. Writing in the Journal of Neuroscience, they showed that units of motor memory are not so binary after all, but instead a mixture of both the intrinsic and the extrinsic.

“There’s no question that our actions are inherently spatial, but the nature of the coordinate frame used in motor memory to represent space for action planning has been hotly debated,” explains Smith. “The predominant idea had been that in memory we maintain separate intrinsic and extrinsic representations of action and translate between the two when necessary. But our work shows that memory representations are combinatorial rather than separate.”

Individual neurons in several different motor areas of the brain encode multiplicative combinations of intrinsic and extrinsic representations, a property that neurophysiologists have called gain-field encoding. This much was known before, but it was thought that gain-field encoding simply provided a way to translate between intrinsic and extrinsic representations.

“We found that this gain-field encoding, which leads to a combinatorial representation of space, is not simply an intermediary in the transformation between representations, but is in fact the encoding on which motor memories are based,” says Smith. “This suggests that the neurons which display gain-field encoding are the same ones that store the motor memories associated with the actions we learn.”

The study, seemingly abstract, plays right into Smith’s larger game plan. He and his research group at SEAS are trying to figure out the body’s motor system the way a mechanic would: that is, well enough to be able to fix or temporarily repair it when it becomes damaged.

A neurodegenerative disorder resulting from a stroke or from a condition like Alzheimer’s disease can make the act of picking up a cookie nearly impossible. But how does one go from an abstract theoretical model about encoding motor memory to something an engineer, a person interested in designing and building actual stuff and collecting real-world data about how we move, might more readily recognize?

The answer lies in a simple room slightly bigger than a walk-in closet. Near the entrance to Smith’s lab, an alcove space is outfitted with a table, a monitor, an adjustable barber chair, and a digital pen and pad. The simple setup allows Smith and his team to record movements and to train participants to make hand motions based on visual cues.

Smith’s lab is one of the few at SEAS that relies on human trials. In the facilities surrounding his, engineers have built tiny robotic insects, lungs-on-a-chip, and an artificial jellyfish made of a rat’s heart tissue and silicone. Yet, despite its name, the work at the Neuromotor Control Lab seems far removed from the snap, crackle, and pop of actual neurons, as there are no neural head meshes or electrodes in sight. There are no brains in jars or neural tissue strands in glass petri dishes. Smith, who has an M.D. as well as a Ph.D. from Johns Hopkins, spends considerable time explaining how it all makes sense.

In the case of this new theory about intrinsic and extrinsic action, Smith’s motion recording setup provides a simple yet powerful means to collect large amounts of data—millions of individual movements—that elucidate the algorithms and neural representations by which we learn to control our actions.

Jordan Brayanov, a graduate student at SEAS, excitedly explains where all of this work is ultimately headed: helping those suffering from brain injury.

“You cannot break real human brains for science, and it is difficult to work with patients who are already exhibiting cognitive deficits, so our lab is set up to mimic these conditions in healthy people—in our case, a lot of Harvard undergraduates,” says Brayanov. “Understanding how our bodies learn to reach and grasp provides us with insights about how the nervous system works. Just as importantly, we can start to see what may be happening when it’s not working, when a person has some kind of motor disorder as a result of neurologic disease.”

Motor dysfunction remains one of the most debilitating of health problems, and it is often the hidden deal breaker behind the nursing home placement and loss of independence for patients with Alzheimer’s, which most people associate with declining mental abilities and deficits in declarative memories rather than motor skills.

“It’s actually not so much the declarative memory loss that leads to having to institutionalize someone with Alzheimer’s, but the inability to do the most basic motor tasks, like dressing or eating,” explains Smith.

Armed with new insights from the lab, Smith and his team can offer guidance to others who are developing new ways to treat motor problems.

They’re placing their hope in noninvasive techniques that use magnetic fields or direct current to selectively increase or decrease the neural plasticity of isolated populations of neurons—no skull drilling required.

“These techniques have shown some promise for potentially boosting selective neural activity to stave off the onset of motor deficits,” says Brayanov. “They’re relatively crude right now. They can’t yet zero in with millimeter accuracy on specific brain areas, but they will get better and better.”

Therapeutic success, however, also requires clinicians to know which neurons to stimulate, and when.

In essence, Smith, Brayanov, and their colleagues are trying to write part of the instructional manual that doctors will one day use to help combat neurodegenerative diseases, much in the same way other engineers might provide the schematics for an artificial hand.

“If we can do that, we can potentially provide a boost in quality of life as well as a savings in healthcare expenditure,” says Smith. “Even if it only means staving off a motor deficit for six months, in the case of a progressive neurodegenerative disease like Alzheimer’s, that’s still six months more of independent living.”

###

This work was supported by grants from the McKnight Endowment for Neuroscience, the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, and the Wallace H. Coulter Foundation.

Topics: Bioengineering

Cutting-edge science delivered direct to your inbox.

Join the Harvard SEAS mailing list.

Scientist Profiles

Maurice Smith

Gordon McKay Professor of Bioengineering