News

Harvard College Engineers Without Borders want to help the residents of Pinalito identify a long-term, sustainable solution to their water troubles. (Photo by Casey Grun.)

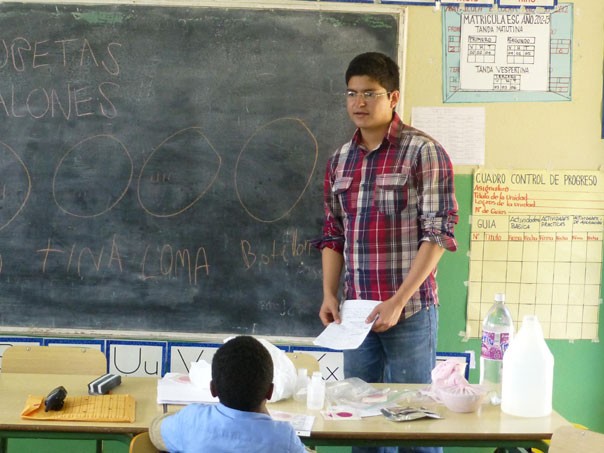

Manuel Ramos '14, Leah Gaffney '15, Tunde Demuren '15, and Dipti Jasrasaria '16 meet with elementary school children in Tireo Abajo to discuss water sanitation and the prevention of waterborne illness. (Photo by Casey Grun.)

For almost anyone, staring down a well at a pump clogged with sediment would mean bad news. For the residents of Pinalito, in the Dominican Republic, it meant they might have to drink from the river—water teeming with bacteria. For the Harvard College Engineers Without Borders (HCEWB), however, it meant the chance to brainstorm a slew of solutions—and determine which would work best.

This past January, the team of students, led by Casey Grun '14 and Tunde Demuren '15, ventured to Pinalito for 9 days to learn about the village’s resources and needs. The clogged pump had been installed improperly, they noticed, leaking water out and sediment in, and the original contractor was long gone. Pinalito is a community so rural that it doesn’t show up on Google Earth, and the tiny population consists of only about 20 to 30 permanent households. The economy is based on agriculture, with an average income of only about $7.50 a day. Not only did 100 villagers need access to clean water; they needed a long-term, sustainable solution that they could own and maintain themselves.

HCEWB, the Harvard chapter of the humanitarian organization Engineers Without Borders, USA, seeks to contribute to environmentally sound and economically sustainable engineering projects internationally, while promoting global consciousness among students here on campus. Supported in part by a Nectar grant from the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS), the group also develops programming and builds mentoring relationships among engineers and students in the Cambridge area.

"Today's largest engineering challenges are in global infrastructure and how this infrastructure can meet the needs of the 7 billion people who live on Earth," says the group's adviser, Christopher Lombardo, who is Assistant Director for Undergraduate Studies in Engineering Sciences at SEAS. "Student groups like Engineers Without Borders provide a mechanism for students to make global contributions during their college education."

"The experience they gain by working on these projects also makes these students highly competitive for employment with companies or institutions that are internationally focused or have offices worldwide," Lombardo adds.

HCEWB had first traveled to the Dominican Republic in 2007 on the suggestion of the Constanza Medical Mission, a Massachusetts-based Catholic charity that was treating many waterborne illnesses there and was looking for an engineering-based solution to the problem.

The Harvard group began working to improve the contaminated water supply in the village of Tireo Abajo, just outside the small city of Constanza. By the summer of 2011, they had distributed point-of-use water filters throughout the community. The students were then referred to the nearby village of Pinalito, visiting in March 2012 to assess the community’s general needs, and again this past January.

Karina Herrera '13 and Dipti Jasrasaria '16 measure various parameters of awater source in Pinalito to assess possible contamination. (Photo by Casey Grun.)

In one busy week, the group conducted a detailed land survey with 260 points of interest to create a map of the region using GIS, enabling an in-depth analysis of the geography. The team also tested the quality of existing water sources for the community, including the river, mountain springs, and tinitas—sand-enclosed water pits from which the villagers collected most of their water. They took measurements of the arsenic levels, turbidity, and nitrate levels, as well as fecal coliform bacteria and E. coli in these sources, as they suspected that the waterborne diseases prevalent in the community were contracted from drinking water.

The team found that the sandy tinitas actually filtered out a good portion of the bacterial content of the water. The mountain spring water was the cleanest, but also more difficult for the villagers to access. The residents used this initial data to decide where they should be collecting water in the short term, until the pump has been fixed or replaced; some families are also using biosand filters in their homes.

For the students working on the project, says Grun, "The biggest challenge is the constant tension between urgency and prudence. The natural inclination is to want to do something as quickly as possible, but we want our solution to be effective and sustainable—and this requires time to do a careful analysis and design."

In addition to the engineering goals of the trip, the Harvard students took time to teach lessons on water quality in Spanish at three different schools to children aged 6 to 13. They designed and presented a curriculum covering water purification and good sanitation behavior, and demonstrated the use of Petrifilms to compare bacteria compositions in different water sources. They even created a comic book chronicling the adventures of Señor Agua, or “Water Man,” against a villain who contaminates water sources. Parents were included in this educational initiative, too, through a water forum teaching water treatment and sanitation.

Diego Huerta '15 leads a presentation at a school in Pinalito describing simple experiments that can detect the presence of bacterial contaminants in water. (Photo by Casey Grun.)

Throughout the entire process, HCEWB ensured that there was open communication with the community.

“Though the Harvard students may be separated geographically and culturally from Pinalito during our academic semesters, we really work hard to form deep connections with our local contacts and ensure all decisions are made jointly,” says Grun, who is studying biomedical engineering and computer science at Harvard.

Before leaving Pinalito, for instance, the Harvard team held a community meeting at the local school explaining the results of the water testing and discussing possible solutions to the water problem. Together, the group determined that their most viable options might be to dig a well near the river, dig a well further uphill, pipe water from a faraway spring, or restore the old, nonfunctional well. A key goal is to ensure that the project is sustainable and operational in the long run, without the students’ involvement.

Here in Cambridge, the students are now hard at work performing an in-depth analysis of the four possible solutions, using the data they collected on elevation gradients and water table depths to design a feasible plan. They regularly call their contacts in the Dominican Republic to check on conditions and listen to the community's feedback on their proposals.

"It's been very exciting to work on a 'real-world problem,'" Grun says, "but it's a weighty responsibility as well. The stakes are higher. Our actions, positive or negative, have a measurable effect on the health and well-being of the residents of Pinalito. This isn't the case for our exams or problem sets, which makes it both inspiring and intimidating."

The group has four months to evaluate the options and decide which is the best to implement before their next trip, in the summer.

Topics: Student Organizations, Environment, Awards

Cutting-edge science delivered direct to your inbox.

Join the Harvard SEAS mailing list.