News

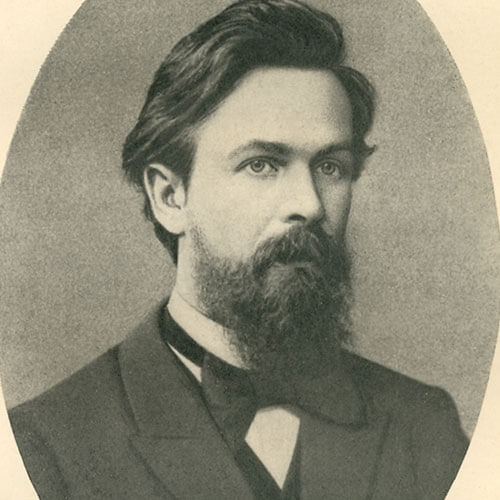

A century ago this week, Mathematician Andrey A. Markov delivered a lecture that day to the Imperial Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg on a computational technique now called the Markov chain.

The Russian Revolution of 1917 was called the “Ten Days That Shook the World,” the title of a book by foreign correspondent Jack Reed, Class of 1910.

But how about the one day in Russia that shook the world, and still does? That was Jan. 23, 1913, a century ago this week. Mathematician Andrey A. Markov delivered a lecture that day to the Imperial Academy of Sciences in St.Petersburg on a computational technique now called the Markov chain.

Little noticed in its day, his idea for modeling probability is fundamental to all of present-day science, statistics, and scientific computing. Any attempt to simulate probable events based on vast amounts of data — the weather, a Google search, the behavior of liquids —relies on Markov’s idea.

His lecture went on to engender a series of concepts, called Markov chains and Markov proposals, that calculate likely outcomes in complex systems. His technique is still evolving and expanding. “This is a growth industry,” said Boston-area science writer Brian Hayes. “You really can’t turn around in the sciences without running into some kind of Markov process.”

Hayes writes the “Computing Science” column for American Scientist magazine and delivered one of three lectures about Markov on Wednesday. The session at the Maxwell-Dworkin building, “100 Years of Markov Chains,”was the first of three symposia this week in ComputeFest 2013, sponsored by the Institute for Applied Computational Science at the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS).

There are close to 200 lectures, classes, performances, and workshops during Harvard’s Wintersession this January, a quickly evolving tradition of freewheeling intellectual stimulation between semesters. But only one event celebrated the centenary of a landmark idea.

Before Markov, said Hayes, the theory of probability involved observing a series of events that were independent of each another. The classic example is flipping a coin, an activity that makes probability easy to calculate.

Markov added the idea of interdependence to probability, the notion that what happens next is linked to what is happening now. That creates what Hayes called a “chain of linked events,” and not just a series of independent acts. The world, Markov posited, is not just a series of random events. It is a complex thing, and mathematics can help reveal its hidden interconnectedness and likely probabilities. “Not everything,” Hayes told an audience of 100, “works the way coin flipping does.”

Read the entire article in the Harvard Gazette

Topics: Computer Science, Applied Mathematics

Cutting-edge science delivered direct to your inbox.

Join the Harvard SEAS mailing list.