News

Some physicists spend their lives obsessed with questions about the possibility of parallel universes, or of travel at the speed of light.

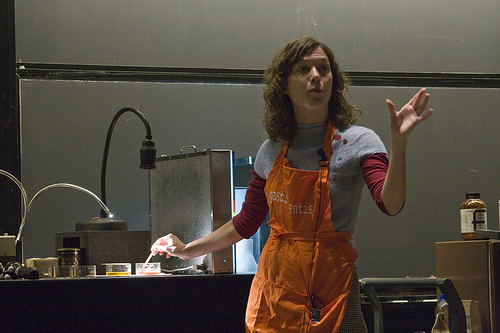

Amy Rowat is obsessed with the mechanical properties of the tiny cell nucleus, and how changes in its shape affect the cell’s physiological function.

Amy Rowat is obsessed with the mechanical properties of the tiny cell nucleus, and how changes in its shape affect the cell’s physiological function.

She also is applying her training as a soft-matter physicist to the question of how to make the perfect pie crust.

Rowat is a postdoctoral fellow in Harvard’s Department of Physics and School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS), and her principal research uses microfluidic tools, in which liquids are forced through channels much smaller than a human hair, to look at single cells, particularly the cells’ nuclei. She is using these tools to explore the largely neglected mechanical aspects of cell biology.

But food, in all its forms, also peaks her scientific interest. What at a molecular level, she wonders, makes a truly flaky pie crust flaky?

Few people see the world, or cooking, the way Rowat does. “Food is essentially cells and nuclei,” she says. But over the past four years as a postdoc at Harvard, Rowat has been using the principles of physics to advance our basic understanding of how the structure of a cell affects its function – and at the same time she’s been using the physics of food and cooking to get people excited about science.

(Rowat, in fact, is one of the developers of a new Gen Ed course that will teach soft-matter physics with, among other things, cooking demonstrations by world-renowned chefs. During the 2010-11 academic year she will be one of the people leading the course.)

This is the first in a series of articles about a few of those young postdocs on the verge of launching their independent careers.

Rowat’s path to a Harvard physics lab began in Guelph, Ontario, where as a child she was fascinated with biology. “I never had chemistry kits or my own microscope, but I really loved to build things and I was really curious about nature and the world around me,” Rowat says.

When Rowat began her undergraduate education at Mount Allison University in New Brunswick, she was drawn to questions in biophysics, the study of biological molecules and the larger structures they assemble into, even before she knew what biophysics was.

She had planned to major in biology until a physics class changed her mind. “My [physics] professor was fantastic and developed this course and style of teaching where all the students were engaged doing experiments and solving problems, and I thought that was challenging and exciting,” she recalls.

Working in a research lab during her summers also had a huge impact on her, she says. “Unless I had the opportunity to work in a science lab as an undergraduate, I would have assumed from science classes that science was not a very creative subject,” she says. But during one impactful summer in the research lab, Rowat created and studied thin layers of polymer films. “I developed a fascination with membranes,” Rowat says. She went on to earn an undergraduate degree in physics – with minors in French, Asian studies, and mathematics.

Her graduate work, conducted in the laboratory of Ole Mouritsen, at the Technical University of Denmark and University of Southern Denmark, took her into the world of human biology. She worked on biomembrane physics, conducting experiments in which she deformed the nucleus and nuclear envelope of live cells. This research helped reveal the mechanical properties of the nuclear envelope, and also inspired Rowat to think more about what was going on inside of the nucleus, within the context of the whole cell.

“I decided that the nuclear envelope and nuclear membranes would be a great [doctoral] topic because there’s very little that’s understood about the physical properties of the interface between the cytoplasm of a cell and the cell nucleus, which is where the important, essential-to-life processes happen,” says Rowat.

After completing her Ph.D. at the University of Southern Denmark, Rowat joined David Weitz’s lab in Harvard’s School of Engineering and Applied Sciences and Department of Physics because she was interested in working on problems regarding cell mechanics and in developing new microfluidic technologies. She currently uses microfluidic tools for single-cell studies, and recently developed a microfluidic tool to trap single yeast cells, which are widely used in biology as a model system.

Thus far, Harvard's Office of Technology Development has filed three patent applications on behalf of Rowat and co-inventors for microfluidic-related work.

In 2007 Rowat proposed a new topic for the Harvard Holiday Lecture Series: pizza.

“I said, ‘Have you ever done a topic on food? I think that would be really popular because everyone loves food,’” she remembers. The lecture title was “The Science of Pizza,” and the talk was a hit. In 2008, Rowat and her colleagues collaborated with a local chocolate company that provided taste samples for that year’s lecture. “Each person was doing their own science experiment using their senses. We tried to get across what it’s like to be a scientist and what a scientist does,” she says. “You make observations, you come up with creative ideas to solve problems or interpret your results.”

For Rowat, learning the answers to basic questions about the physics of food and cooking have helped her to understand more about the underlying science she’s researching, and she feels strongly about spreading the word to others that science is an exciting, creative, and dynamic field.

For Rowat, learning the answers to basic questions about the physics of food and cooking have helped her to understand more about the underlying science she’s researching, and she feels strongly about spreading the word to others that science is an exciting, creative, and dynamic field.

“I think that when there’s scientific illiteracy, that can lead to many social problems,” says Rowat.

The postdoc has also used food for topics in the weekly Squishy Physics Lectures, a series of informal research presentations devoted to soft-matter physics. “It really is a good community-building event, where people from different labs come together and interact,” says Rowat.

Lecturers and listeners of the squishy physics series come from many area universities and even other countries, some are from as close as the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and others from as far away as Germany, Israel, and Korea. “I think that’s really important in a university, to have these intellectually stimulating discussions and conversations,” says Rowat.

One of the most memorable lectures for her was a seminar during Oktoberfest. “I invited a brewer and a yeast biologist,” says Rowat. She developed the idea during a time when her research was working with yeast and engineering devices to study yeast lineages.

Considering her postdoc period, Rowat says that Harvard “has been a fantastic place. It’s been a great place to be able to discuss my research with really great colleagues, both within my group and the Harvard community,” she says. Her main philosophy, to take risks and pursue creative passions and ideas, has led Rowat not only to cutting-edge research in soft physics, but also to enjoy running, yoga, and of course cooking meals for friends in her limited spare time.

“Sometimes I’ll be cooking with more of an artistic perspective,” she says. “There are other times I’m thinking much more about what’s going on at the molecular level and how I could make a flakier pie crust.” Her most recent creation was a gooseberry pie.

So is she ultimately more passionate about the soft-matter physics that underlie that flakier pie crust, or the joy of cooking? Rowat won’t say. But if she could have lunch with either Michael Faraday, the 19th century chemist and physicist whose photograph Albert Einstein kept in his study, or Julia Child, she replies:

"I’ve heard Julia Child is quite a character.”

Topics: Cooking, Bioengineering, Applied Physics

Cutting-edge science delivered direct to your inbox.

Join the Harvard SEAS mailing list.